Introducing a few of the earth’s movers and shakers

Have you ever wondered who all the critters that live in the undergrowth of the forest and under the rocks in your garden are? Allow me to introduce a few of our silent and often unseen neighbours – those unlikely allies who quietly break down fallen leaves, defend our gardens from potential pests and help us to grow food.

Worms

Earthworms are one of the most efficient composters on the planet. Moving through the soil, these animals help to break down an enormous portion of organic material. They increase both aeration and water penetration into the soil, making more hospitable conditions for other organisms.

It is thought that the glaciers actually wiped out the earthworms from Canada, and nearly all earthworm species now found here are actually European species that were re-introduced in the ballast from some of the first ships to sail from Europe. We now see that non-native species significantly disrupt natural ecosystems and we should take care not to spread them beyond the garden.

Salamanders

Many amphibians are very effective predators, and salamanders are no exception. They are very welcome allies in the garden, and eat all sorts of creatures, from insects to worms and snails. Like most other amphibians, salamanders can only be found where there is a good level of moisture, generally with plenty of ground cover like under rocks, logs and dead leaves or thick mulch, typically in wooded rural areas. You can help them by keeping an area with plenty of mulch or leaves in your yard – this is especially important over the winter.

What’s the difference between a newt and a salamander? Newts are actually a sub-set of salamanders that generally lead a more aquatic life than other groups of salamanders. So: all newts are salamanders, but not all salamanders are newts.

Species spotlight

The Yellow-spotted Salamander is one of the many salamander species found in Canada. These handsome critters are usually black to dark grey or brown as adults, with two bands of yellow spots running down their back.

Bees (ground-nesting)

While most people think mainly of Honeybees as our star pollinators, Canada is actually home to over 800 species of native bees. Many species live in underground nests, burrowing into the earth to build their homes. Some of the most recognizable groups such as bumblebees, sweat bees, mining bees and squash bees all build ground nests. Most ground-nesting bees are solitary species, and either don’t have stingers or wouldn’t sting unless attacked, because they don’t have a colony to protect.

Did you know: 70% of the world’s species of bees don’t live in hives but build their nests underground?

Help the bees

One of the easiest ways to help ground-nesting bees is to simply be aware of their presence. Their favourite places to live are in well-drained, south facing slopes with sparse vegetation. Squash bees actually tend to build their nests as close to squash or pumpkin plants as possible – keep an eye out for pencil-sized burrows and try to avoid tilling up areas that are favourable for bees. They depend on these nests to rear the next generation of our pollinating friends! Never use chemical pesticides if you have bees nesting in a nuisance part of your lawn: simply watering the area regularly will encourage them to move elsewhere.

Millipedes

Millipedes do not have 1,000 legs, whatever their name may suggest. They are actually born with only three pairs of legs, but can grow up to 200 over their lifespan. Millipedes are defined by having a segmented body, rounded along the top, with two pairs of legs on each segment. They curl up when scared or dead. Millipedes are very efficient detritivores (eating fallen leaves and other dead organic matter) and help in breaking down organic material down into nutrient-rich soil for plants.

Millipedes are some of the longest-lived arthropods and can live for several years! They are also thought to have been some of the first animals to live on dry land thanks to a 428 million-year-old millipede fossil found in Scotland.

Unlike centipedes, millipedes do not bite or sting, however some species secrete stinky chemicals as a defence, so it is still not advisable to handle them.

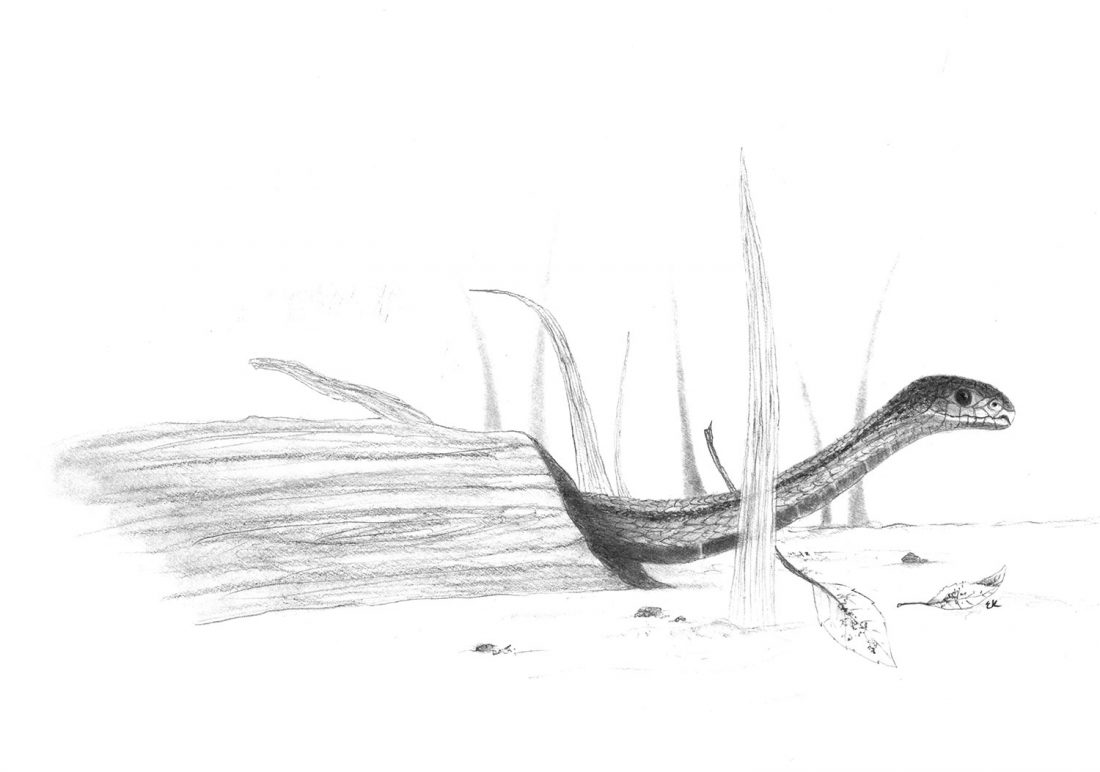

Snakes

Snakes are keystone predators in the undergrowth – they feed on everything from amphibians to insects and snails, with a few species feeding on rodents. While there are 26 species of snakes native to Canada, several species are suffering from loss of habitat and one has been extirpated (no longer found in Canada). Keeping areas of undergrowth undisturbed, as well as providing over-wintering areas can help these critters to thrive.

Species spotlight

The Red-bellied Snake is a small but mighty gardening ally! It has special adaptations to its jaw and teeth that help it to remove the shells from snails – one of their favourite things to eat! These tiny snakes are completely harmless to people, but are very helpful at keeping snail and slug populations down in your garden.

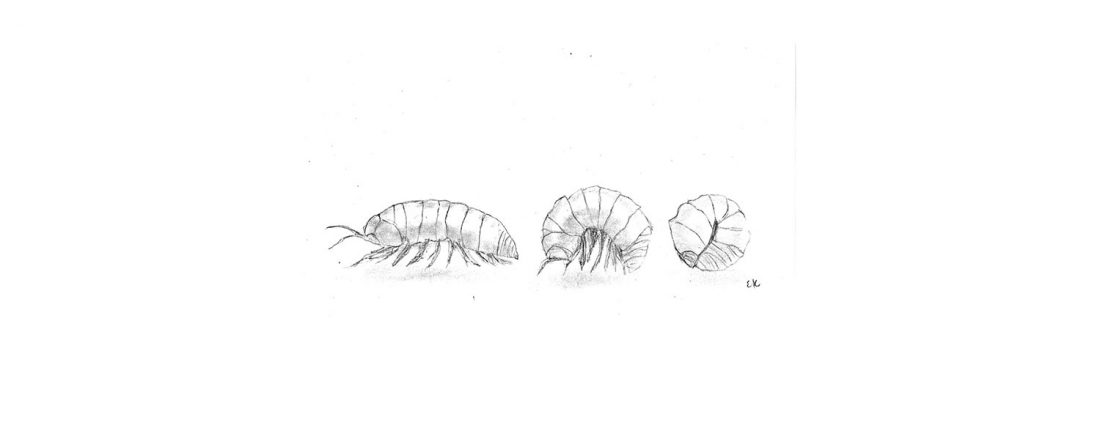

Pillbugs

Known variably as the roly-poly, the armadillo bug and the woodlouse, pillbugs are another group of detritivores. As their scientific name (Armadillidiidae) suggests, many pillbug species are known to curl up into a ball, especially when frightened.

Pillbugs can ingest metal ions, including heavy metals such as lead, arsenic, zinc and cadmium. They can crystallize these metals in their midguts and serve a crucial role in ridding soil of these contaminants.

Pillbugs are crustaceans and are therefore more related to shrimps, crabs and lobsters than they are to any insect. As crustaceans, these creatures breathe using gills and need very high moisture levels to survive.

Submitted for Harrowsmith magazine’s Spring 2019 issue and reprinted with permission.

1 comment

Very interesting information