Not only do marine protected areas safeguard biodiversity, but with nature taking the lead, MPAs boost commercial fisheries and help lock in massive amounts of carbon.

HERE’S A THOUGHT EXPERIMENT.

What if, instead of trying to fix nature, we let nature fix us?

Take the ocean as a case study. It’s in alarming shape, the result of an ensemble of assaults from humans. To date, just 2.7 per cent has enough protection from those assaults, despite a global goal of 30 per cent by 2030.

The ocean is absorbing most of the extra heat our carbon-drenched atmosphere is holding onto, but the ocean is also soaking up boatloads of the carbon itself, changing its acidity. The result is an ocean that’s becoming warm, breathless and sour — and a lot harder to live in for marine creatures.

To add to the misery, we’ve appallingly mismanaged the global fishery, taking too much from too many places too fast, destroying great swaths of seabed habitat in the process. So, we’re scooping out masses of life at the same time as we mess up marine chemistry.

What to do about it? And where?

Now, for the first time, we have a detailed framework, contained in a blockbuster paper by the Dalhousie University marine ecologist Boris Worm and 25 others, published in March in the journal Nature.

It was a statistical slog. First, the authors subdivided the entire global ocean into blocks of 50 by 50 kilometres. Then they hunted for the nitty-gritty about each block, scraping information from satellite data sets, global fishing records and scientific analysis.

“We couldn’t have done it five years ago because we didn’t have the satellite data,” Worm told me recently.

Three post-doctoral students, Reniel Cabral, Darcy Bradley and Juan Mayorga, all with the environmental market solutions lab at the University of California Santa Barbara, had the computer skills needed to wrangle the numbers.

“They were magicians,” Worm said. “These three young heroes systematically chewed through the problems.”

The team asked novel questions: What assemblage of life was in each block? How distinct was that life in evolutionary terms? What were the specific threats?

Then they developed an algorithm to assess what would happen to life in each block without human activity — fishing, shipping, mining, oil and gas exploration, and so on. What if those pieces of the ocean were left to their own devices? And then the team looked at possible benefits through three lenses representing the planet’s three most pressing problems: biodiversity loss, food insecurity and climate disruption. It was a radically different way of analyzing the ocean. Rather than fishing and conservation being sworn enemies, maybe they could help each other. So, don’t make marine protected areas in order to hinder fishing; make them in order to enhance it.

And what if those restored parts of the ocean could also be a cheap and easy way to help solve the carbon crisis by leaving carbon stores intact in the ocean floor and allowing marine plants to breathe in emissions?

It turns out, it works. Dramatically increasing protected areas could boost fishing catches, save species and also store carbon. A key to saving nature — and ourselves — is to leave it alone.

“This is not moving the needle. This is fixing the problem,” Worm said.

The trick is to figure out which bits of the ocean to protect. In other words, where does nature have the greatest ability to heal herself? And rather than a one-size-fits-all blueprint, the framework is flexible enough to adapt to different countries’ priorities. But, the authors point out, if countries work together, the benefits can double.

The paper is part of a new philosophy in conservation called naturebased solutions. It requires faith in nature and in the evolutionary processes that created an exquisitely balanced nature in the first place.

The nature-based solutions idea has been gestating for several years and is now coming into its own internationally. A recent study found that strategically restoring natural spaces on land could soak up nearly a third of the extra carbon emitted into the atmosphere since the Industrial Revolution. The key is to restore the right ones.

To me, this is about more than healing the air, the land and the sea. The idea holds out the potential of humanity healing itself, too. Rather than simply using nature up as we have for so long, or even setting some aside as pretty preserves, this is about recognizing that nature has her own wisdom.

Once we name that, we have to honour it. That means resetting our relationship with nature, steadfastly refusing to revert to a time when we failed to recognize her power. And that may hold out our best chance of survival.

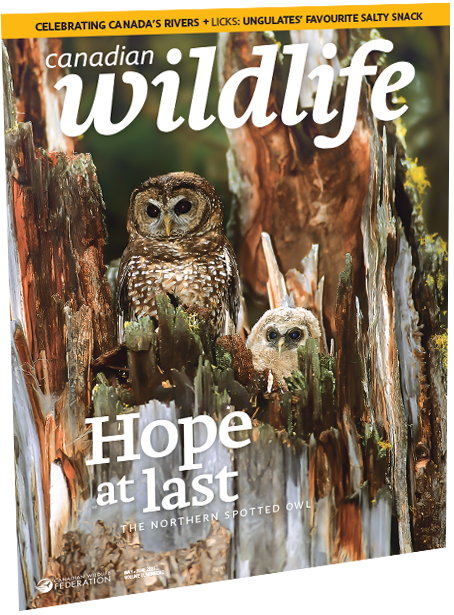

Reprinted from Canadian Wildlife magazine. Get more information or subscribe now! Now on newsstands! Or, get your digital edition today!

1 comment

Pretty obvious what s is necessary