Why do mockingbirds mimic other birds’ songs? To boast? To befuddle? Some scientists think it’s to attract and impress potential mates

Each night as daylight transcends into darkness over the cactus-filled desert habitat in the Mexican state of Baja California where my wife and I now spend our winters, we are serenaded for a brief moment by the lovely song of a northern mockingbird. One has made its nightly roost in the large candelabra cactus right outside our front door.

Found in a variety of habitats throughout southern Canada and most of the United States and Mexico, from cities to deserts, this highly conspicuous, long-tailed songbird (Mimus polyglottos) can be heard singing throughout much of the year, and unlike most birds, even into the night. Most interesting though, the aptly named mockingbird is also the most accomplished mimic in the bird world.

While the percentage of a mockingbird’s total song consisting of mimicry ranges from five to 15 per cent, some of its song is composed entirely of imitations of other species. An individual mockingbird has the ability to imitate, one after the other, dozens of common North American species, such as the blue jay, the American robin and the northern cardinal.

One gifted mimic recorded by Cornell University ornithologists was able to imitate 30 species. Another mockingbird in Boston imitated the songs of 39 species, the call notes of 50 and the sounds of tree frogs and crickets. One individual in South Carolina mimicked 32 species in just 10 minutes!

It is not just songs and calls that are imitated. In Wichita, Kansas, in 1923, a mockingbird was heard to imitate the songs and calls of the birds in that particular locale before rendering a perfect imitation of a red-headed woodpecker drumming with its bill on metal.

Mimics can even imitate a species not found in their normal range. A mockingbird in Texas was once heard to mimic a green jay, a species found only in the Rio Grande Valley some 500 kilometres to the south. In another case, two nesting males in northern Lower Michigan included as part of their respective repertoires imitations of 14 and 15 different species, some of which belonged to birds that did not even occur that far north. Whether these non-local songs were picked up directly from their owners during a wintering period there or passed on through generations of mockingbirds is not known.

So why do some birds mimic others, or any sounds for that matter?

A simple explanation put forward is that mimicry simply serves as an outlet for a bird’s surplus urge to sing. Some have suggested an element of play is involved. Still others believe mimicking species that incorporate a number of other species’ songs and calls into their repertoire may be revealing information about their age and their success at achieving such longevity. Perhaps enlarging its repertoire, even with non-avian sounds, may confer reproductive advantages upon the mimic. Some studies indicate that mockingbirds with larger repertoires of other species’ songs are more likely to attract mates and, thus, pair earlier and exclude competitors from within their own species.

Whatever the reason for it, mimicry is most certainly a fascinating aspect of bird life. Unless you have a great ear for bird songs and calls, chances are you have been fooled by a mimic before — and it probably will not be the last time.

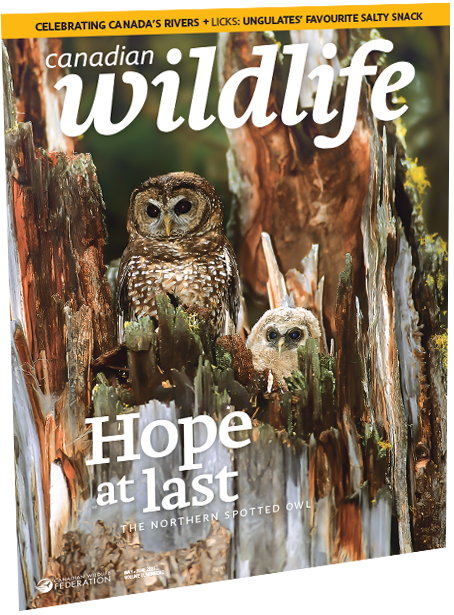

Reprinted from Canadian Wildlife magazine. Get more information or subscribe now! Now on newsstands! Or, get your digital edition today!

3 comments