We know frustratingly little about these massive creature’s movements.

We know even less about where they congregate and why, how they choose their migration routes and what causes these to change, sometimes gradually and other times with amazing suddenness.

We do not know—and we need to—how the world’s whale populations are responding to human dangers like chemical and sonic pollution, marine traffic, underwater mining and drilling, commercial fisheries and, of course, rising ocean temperatures.

Why Do We Need to Know These Things?

One of the most effective measures protection authorities regularly deploy are mitigation measures like vessel speed reduction, shutdown of acoustic sources in sensitive zones and other marine protection areas. To ensure these measures are successful, we need to be able to reliably identify which areas are frequented by marine mammals for feeding, communing and calving.

The gaps in our knowledge about Canadian whales are enormous, even concerning the most common species.

- Blue Whales we know come into the Gulf of St. Lawrence every summer and they feed in the Tadoussac-Saguenay area of the north shore; otherwise, we really don’t know where these Endangered whales go.

- On the west coast, Endangered southern resident Killer Whales hunt salmon in the Salish Sea near Vancouver, and range down the West Coast to California but beyond that, surprisingly little is known about their lives or what is causing their numbers to dwindle.

- Gray Whales too, there’s a summer group that congregates every year to feed off the coast of Vancouver Island, but we simply don’t have good information about where they come from, or where they go after.

- Sadly, the same is true about Humpbacks a little further up the BC coast. And in Canada’s Arctic waters, where even less is known about whale behaviours, oceanic changes are happening more quickly and more devastatingly than anywhere else.

A Vivid Example: North Atlantic Right Whales

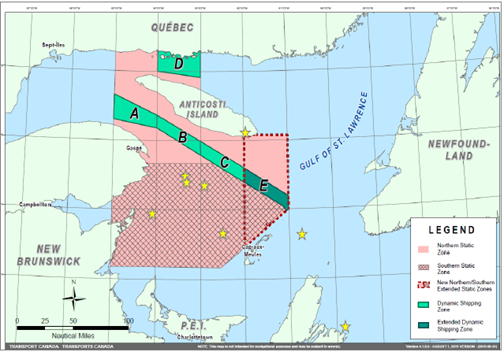

Canada’s Right Whales are a vivid example of the problem. As early as 2010, there was evidence of changing feeding and migration patterns—researchers in the Bay of Fundy had noticed a significant drop in numbers and early research suggested that the local population might now be gathering in the Gulf of St Lawrence. There was evidence too that conflicts between whales and humans were on the rise and they would increase in the Gulf where there is so much shipping and commercial fishing activity.

Sadly, the information was not acted upon until it became an emergency during that grisly summer of 2017. That’s when Canadians started to hear disturbing reports of whales being struck by ships and others being entangled in and dragging heavy fishing lines and gear, wounded, weary, weak, their vitality and strength slowly ebbing away until they succumb. That summer Canadians were alarmed by the death of 12 Right Whales in Canadian waters, and another seven died in US waters to the south. That summer was what some experts call “an unusual mortality event.”

All this human-made destruction was occurring to one of the most-studied whale species in the world, of which there are no more than 350 individuals. And still, researchers are only able to observe half the population in any given year. No one knows where the other half go. There is so much to learn.

~Sean Brillant, CWF Senior Conservation Biologist of Marine Programs

To its credit, the Federal government acted quickly that summer, collaborating with numerous fisheries, and non-government groups to respond to the crisis, leading to the implementation and enforcement of local fisheries closures and curtailed catches, among several emergency measures. However, everyone involved would agree that it was not an ideal response: the measures were ad hoc, and they had come after numerous mortalities had already occurred; and not ideal because of the costly impact of these necessarily drastic, sudden and unplanned limits on local fishing communities and their livelihoods. This is an age-old problem.

Government’s Role in Managing Natural Resources

Typically, it is any government’s job to manage natural resources in environmentally and economically sustainable ways. Too often in the past, evidence of an environmental conservation problem has not been sufficient cause for a government to change the way human activities are managed. Generally, action only happens when the problem reaches crisis conditions. The problem with this model is it depends on reactive measures created under extreme pressure to address a deeply rooted systemic problem while at the same time trying to protect the livelihoods of those working in the sector. It is a near-impossible task to reconcile them in the short-term.

Typically, it is any government’s job to manage natural resources in environmentally and economically sustainable ways. Too often in the past, evidence of an environmental conservation problem has not been sufficient cause for a government to change the way human activities are managed. Generally, action only happens when the problem reaches crisis conditions. The problem with this model is it depends on reactive measures created under extreme pressure to address a deeply rooted systemic problem while at the same time trying to protect the livelihoods of those working in the sector. It is a near-impossible task to reconcile them in the short-term.

That notwithstanding, the longer-term impact of the federal regulations was positive: over the subsequent year, there were zero observed Right Whale deaths as a result of entanglements or ship strikes in the Gulf, and the fishery in the area of highest whale densities returned to normal activity. This demonstrates that not only that government can act on issues of environmental conservation, but that these actions, when proactive, adaptive, and based on science can make a real difference. It is important to note, however, that three Right Whales were entangled in 2018, two in the Gulf of St. Lawrence, and in 2019, there were nine deaths and two sighted entanglements in Canadian waters.

The lesson is clear: sustainable, preventive evidence-based measures will reduce whale mortality risk. It is also clear for that such measures to be in the least effective, we need to know where whales are.

Signs of Progress

Since that lethal summer in the Gulf of St. Lawrence, a lot of time, expertise and money has gone into turning the tide in the battle to conserve Right and other whales in the Gulf. The measured and planned introduction of new federal regulations in 2018 may have led to zero attributable Right Whale deaths and a profitable fishery even in those areas with the highest whale densities.

Since that lethal summer in the Gulf of St. Lawrence, a lot of time, expertise and money has gone into turning the tide in the battle to conserve Right and other whales in the Gulf. The measured and planned introduction of new federal regulations in 2018 may have led to zero attributable Right Whale deaths and a profitable fishery even in those areas with the highest whale densities.

This clearly demonstrates the potential for governments to lead effectively on environmental conservation when they act proactively instead of reactively, and when they implement plans that are science-based, adaptive, and sustainable.

Support for the effort that has delivered real progress came through initiatives such as the combined Fisheries and Oceans Canada and National Science and Engineering Research Council’s Whale Science for Tomorrow initiative, offering five-year funding (2017), and the five-year Canadian Nature Fund for Aquatic Species at Risk (2018) which provided $55 million in research funding over five years). This and other funding led to increased research into whales and their behaviours, into the most effective conservation methods and how to increase our understanding of these mysterious creatures, that is, how we can effectively track and study them.

Now, with these programs reaching their mandated termination, new funding streams must be developed. Important work needs funding to continue.

What YOU Can Do

Sign Our Petition!

Support CWF’s Marine Action Plan – MAP is a major conservation plan designed to make Canada’s ocean safer for marine wildlife. We are asking the Canadian government to continue to invest in research and programs that can help us better understand the range and movement of marine mammals. Knowing where these majestic animals are is critical to ensure their survival. Add your voice and help us get the support we need to help protect and conserve marine animals.

Learn more about the Critically Endangered North Atlantic Right Whale and the CWF Marine Action Plan.