Native plant gardening is an effective way anyone can make a positive impact on their environment.

It creates habitat for wildlife, beautiful greenspace and helps with climate change mitigation. There isn’t a garden too small. If you are in an urban area, balcony and rooftop gardens or community spaces are especially important to migrating wildlife, such as Monarchs or goldfinches, in an otherwise ‘desert’ of concrete and grass lawns.

Freshly mown grass may look appealing to us but it is seen as a desert by many pollinators and other wildlife. I set about changing this by creating a mini-habitat restoration project in my backyard this spring.

I have a confession to make — gardening does not come naturally to me. As of the beginning of this year, I had almost no experience gardening beyond cutting the grass and trimming bushes.

But what I do know is the importance of biodiversity, the human impact on it and the needs of wildlife. For example, pollinator populations are declining due to habitat loss, pesticide use, climate change and increased disease but they are also one of the main beneficiaries of an at-home habitat restoration.

That is why I decided to create an ‘oasis for wildlife’ project in my own backyard.

My Native Garden

I started by researching plants native to my area, the Carolinian zone.

I found out that many plants and seed mixes labelled as wildflowers or pollinator friendly aren’t actually native! The ecoregional planting guides by Pollinator Partnership were especially helpful as I navigated the complex world of native, naturalized and invasive plants.

I purchased seedlings from a native plant nursery as well as perennial seeds of native and naturalized plants in the spring of 2020. I also created a small vegetable garden to further understand the connection between pollinators and our food. Now, I have started to see the fruits of my labour.

I was surprised by how easy and affordable a native plant garden is to maintain. I don’t have to mow as large of an area of lawn, constantly trim or use compost. And I didn’t need to purchase topsoil or fertilizer for the native plants. I found this a welcome respite when we spend so much time on lawn maintenance. Statistics Canada reported on a typical day in 2005 nearly 11 per cent of Canadians aged 30 and over spent time working on their lawn or garden, with the average participant spending more than two hours doing yard work!

Lawns — A Modern Invention

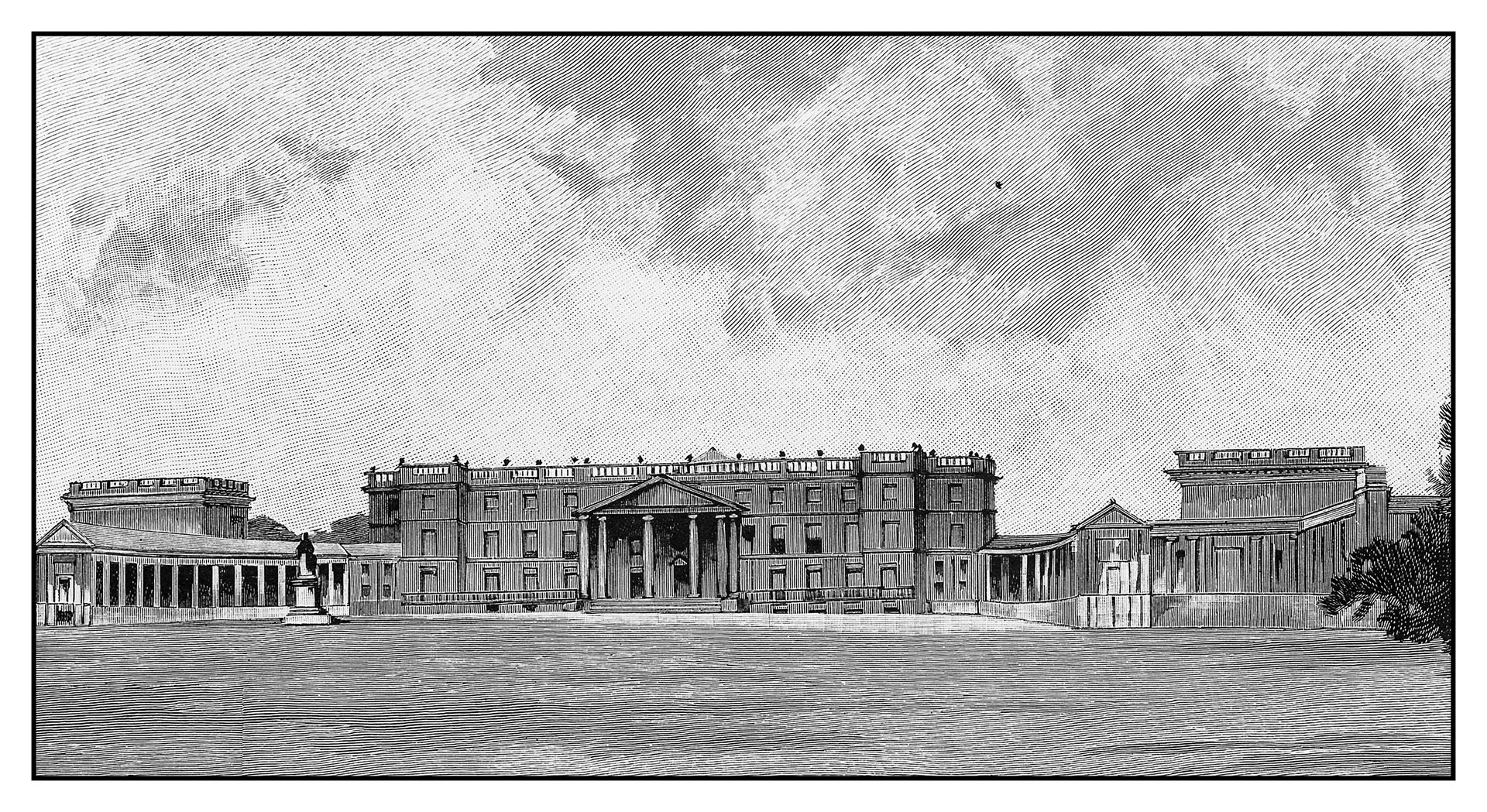

I also learned that the lawn is a relatively modern invention. Mown lawns began with nobility in Europe in the 18th century. It was labour and time intensive and therefore used as a status symbol. This trend was brought to North America by the gentry and was reproduced on large estates, including the likes of George Washington who hired English landscapers to create his lawn.

It wasn’t until the early to mid 20th century, with the rise of suburban neighbourhoods, that lawns became commonplace. This was originally done to mimic upper class housing. It seems less important now that I’ve learned this; a garden adds more curb appeal than a lawn to me.

Part of the Natural Order

Furthermore, native plant gardening helped me understand my local ecosystem. We are used to living apart from the natural world — I think a lot of us see our home as a place exclusively for our family but it would be beneficial for all of us to open up our homes to wildlife.

We had a Northern Cardinal family raised in our yard this year as well as goldfinches, Blue Jays, Red-tailed Hawks and other birds come through. Cottontail Rabbits moved in, Black Swallowtail Butterflies visited alongside a multitude of other pollinators — such as bumble bees, hover flies and beetles.

It’s true; if you plant it, they will come.

1 comment

Wonderful. We need more people to do this