Among European birds, mechanized olive harvests are a serious threat. They are dying in the thousands

The next time you reach for that bottle of olives for your martini or for hors d’oeuvres for a party, you might want to think of this horrifying fate for some of the world’s birds — being sucked up in a huge vacuum cleaner and then sold to rural hotels to be served as delicacies!

According to a recent study published in the prestigious scientific journal Nature this past May by Luis Da Silva and Vanessa Mata of the Research Center in Biodiversity and Genetic Resources in Portugal, more than two million birds are being sucked out of olive trees in Portugal and Spain every year. Olives are harvested from October through January, which coincides perfectly with the migration patterns of songbirds seeking warm climates to spend the winter. The birds roost in the trees during the night, and that’s precisely when the olives are harvested. Olives apparently taste better when harvested at night because the cooler temperatures allow for better retention of aromatic compounds.

Mechanical harvesters, taller than the trees and armed with floodlights and rows of vibrating teeth, move along the rows of olive trees, seizing each one and shaking it violently to loosen the fruit and direct it into powerful vacuums. Blinded and stunned by the bright lights of the vacuum-like harvesting machines, the sleeping birds are literally sucked right off their perches into them.

We’re talking warblers, thrushes, wagtails, finches and robins, including at least a half-dozen species already on the decline for other reasons. The machine operators then sell the dead birds to local rural hotels for human consumption. In one region of Portugal alone, a half-dozen birds are killed each night per hectare of olive tree grove, which amounts to 96,000 birds lost per year. In Spain, an estimated 2.6 million birds are vacuumed up annually.

European birds do not need this added source of mortality. As it is, numbers of farmland birds in that region of the world have dropped by 55 per cent over the last three decades, and there are widespread feelings among the bird conservation community that modern agricultural practices are just as much to blame as illegal hunting in Mediterranean countries like Malta. And it is not just European birds. Millions of migrating birds from the United Kingdom pass right through those countries on the way to their wintering grounds in northern Africa. Who knows how many spend their nights in those olive groves, not to continue their journey in the morning.

Does anyone care? In Portugal, conservation officials want to spend another season counting dead birds before making a decision about banning nighttime picking. The regional government of Andalucía in Spain called for the practice to be stopped and for farmers to cease selling the dead birds to restaurants — but has yet to introduce legislation. And what about those other big olive-producing countries such as France and Italy? Sadly, there does not seem to be much will among them to do anything about the practice at this time. But if we North Americans decide to stop eating their night-harvested, “non-bird-safe” olives and, thus, hurt their pocketbooks, maybe that will get their attention. It certainly worked for dolphin-safe tuna.

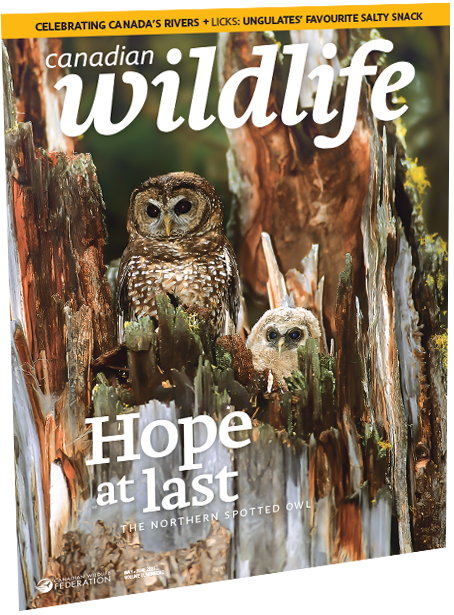

Reprinted from Canadian Wildlife magazine. Get more information or subscribe now! Now on newsstands! Or, get your digital edition today!

2 comments

Night-time picking of olives should NOT be banned since the temperature at harvest affects the end product. The birds just need to be relocated (scared off). Simple noise makers used in the hour before nightfall should shoo most of them away. An additional human worker walking along scaring off birds ahead of the machine may save a few more. Those birds that fail to evacuate can be found in the catch basin of the olive harvester (after the tree is shaken) and be manually removed prior to suction being turned on. It will slow down production a bit, some birds will still be injured in the fall during shaking, and some disease transmission may occur from the human physically touching birds as they are removed from the machine, but overall most birds could be saved without changing requirements for harvesting the orchard. The birds can return themselves to the same trees until the next harvest or migration. The injured can be humanely dispatched. The pre-harvest sounds (and I do recommend using the same sound at all olive orchards) could be learned by the birds as a signal to evacuate. Using direct human encouragement to evacuate and the resulting increased survival rates means that the surviving birds will teach their offspring/community members to leave when the sound is heard, reducing human intervention and farmer’s expense over time. Birds are sensitive to sounds, capable of associating sounds with danger, and are good at communicating warnings to others–let’s use these natural traits to solve this problem.

Re.https://blog.cwf-fcf.org/index.php/en/bitter-harvest/

Those of us who are willing to take action, such as a petition, need to know to whom or to what government ministry the petition can be addressed. Can CWF or David Bird provide some useful feedback? Thank you.