The year 2017 was the beginning of an “Unusual Mortality Event”, wherein 21 Right Whales were killed in the Gulf of the St. Lawrence in just two years.

At this rate, the species will be functionally extinct within the next two decades. Due to major threats like vessel strikes and fishing gear entanglement, these animals are no longer dying of natural causes. This will be the first great whale to be driven to extinction by humans.

So how can we stop these incredible marine mammals from going extinct?

In order to protect these vulnerable animals, we need to know where they are most at risk. This presents a surprising number of challenges. Their distribution and habitat are not completely understood, and not all mortalities are detected or can be examined to determine a cause of death. Furthermore, when a dead whale is found, we can’t be sure of where it died, as carcasses drift on ocean currents and so they can be found far from where they were killed.

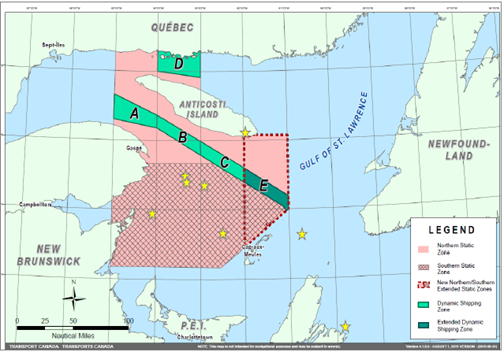

The shipping lane between the Cabot Strait and the St. Lawrence River poses a great risk of vessel strikes to North Atlantic Right Whales. It is divided into dynamic shipping zones (A, B, C, D, E) which you can see in the map as well.

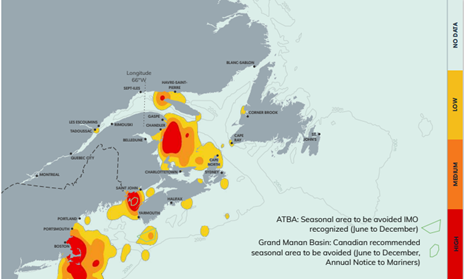

Historically, most Right Whales spent the summer months feeding in the Bay of Fundy and Roseway Basin, off the southern coast of Nova Scotia. Management measures were implemented successfully to ensure protection of the whales in those areas, but in recent years, climate change has driven a shift in Right Whale habitat. Our oceans are changing faster than ever and many species are unable to adapt fast enough. The Right Whales have found new food patches north of their usual feeding grounds. Unfortunately for these incredible mammals, feeding in these new areas has led them into the unprotected waters of the Gulf of St. Lawrence. Climate change has driven the world’s most endangered whale into a death trap; one of the busiest international shipping routes.

While the risk to whales from vessel collisions can be less severe with reduced speed, out team’s research has shown that even smaller vessels at reduced speeds can have lethal impacts on whales. Voluntary 10 knot speed restrictions have been put in place periodically in the Cabot Strait, with very low compliance rates.

While the risk to whales from vessel collisions can be less severe with reduced speed, out team’s research has shown that even smaller vessels at reduced speeds can have lethal impacts on whales. Voluntary 10 knot speed restrictions have been put in place periodically in the Cabot Strait, with very low compliance rates.

Under the Species at Risk Act, it is illegal to harm or kill a Right Whale. Transport Canada has failed to implement effective measures to protect the Right Whales that remain. While fishing areas have been subject to complete closures, jeopardizing the livelihoods of coastal communities, the shipping industry has faced little consequence. Voluntary measures are nothing short of self-serving, and detection-based restrictions create havoc for ships on tight schedules. A mandatory speed restriction in the Cabot Strait would reduce the risk to whales during their migration.

It is our hope that the government and Transport Canada will acknowledge the urgency of the situation and take the necessary actions to save this species.

What can you do?

1 comment

Thanks for brining this to attention of readers.