If asked this question, many Canadians might imagine wheat and canola fields extending as far as the eye can see.

While this image is technically correct – most of Canada’s wheat and canola fields occur in the Prairie region of Alberta, Saskatchewan, and Manitoba -I am referring to native prairie, lands dominated by native grass species, also known as the Grasslands.

With too much rainfall to be a desert and too little rainfall to be a forest, Grasslands exist at the nexus of continents, at places far from large bodies of water. Grasslands occur in many regions around the world, covering about one quarter of our planet. They can be grouped broadly into two categories: the Tropical Savannahs of Africa, Australia, South America, and Indonesia, and the Temperate Grasslands of more northerly and southerly regions across the globe.

Temperate Grasslands have many names. In South America they are known as the Pampas, in Southern Africa as the Veldt, in Hungary as Puszta, and in Eurasia as the Steppe. In the USA, they are known as the Great Plains, and here in Canada as the Prairie.

Temperate Grasslands typically have deep, rich soils and have provided grazing habitat for wild and domestic animals over millennia. In many regions they also provide excellent conditions for growing annual crops, and consequently much of their expansive flattish lands have gone under the plough and are now used to grow crops such as the wheat and canola, which is why we easily envision these crops in our minds-eye image of the Canadian Prairies.

A 2008 report by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN) indicated that temperate grasslands are now considered the most human-altered and threatened ecosystem on the planet, with only 5.5% of these grasslands protected. The plough has reduced native grasslands to a small fraction of their original global distribution.

In the 2010 Ecosystem Status and Trends report of the Canadian Councils of Resource Ministers, native vegetation were estimated to now cover less than 25% of the Prairies Ecozone. Most of this loss of native vegetation occurred prior to the 1990s, but losses, primarily to annual cropland, continue today.

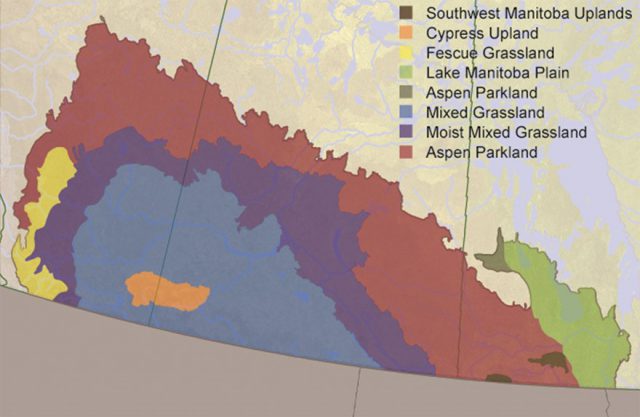

The Prairie Ecozone of Canada spans 465,094 km2, which is almost 5% of Canada’s landmass. It is estimated that over half of the remaining native grassland in Canada is in the Mixed Grass Prairie, which occurs in southern Saskatchewan, Alberta and Manitoba. The map below indicates where the Mixed Grass Prairie occurs.

Where can we still find the wild prairie in Canada?

Although less than one third to one quarter of the original 24 million hectares of Mixed Grass Prairie remains in Canada, this area still contains large tracts of native grassland, primarily occurring on crown lands.

Saskatchewan and Alberta have the lion’s share of our remaining Mixed Grass Prairie, and that is the focus of this blog. Future blogs will feature the grasslands of Manitoba, Ontario, and British Columbia.

The common grasses in the Mixed Grass Prairie include blue grama (Bouteloua gracilis), wheatgrasses (Pascopyrum), speargrasses (Hesperostipa), and June grass (Koeleria macrantha).

The most significant sources of our remaining native prairie grasslands include the Prairie Farm Rehabilitation Administration (PFRA) pastures, the Alberta Provincial Grazing Reserves and Allotments, and the Saskatchewan Community Pastures. These pastures were set aside in Canada’s three Prairie provinces in the 1930s to help reclaim badly eroded soils during the intense drought of the Dirty Thirties. The 85 PFRA lands alone cover a total of 2,256,072 acres, most of which occur within Saskatchewan.

Today, these pastures continue to be managed with the goal of protecting the land from drought, development and intensive cropping impacts, and supporting ranchers. These lands also support a very diverse community of species, including 31 species at risk, such as the Swift Fox and Greater Sage Grouse. It also supports populations of grassland specialists such as the Pronghorn, North America’s fastest land animal.

What Does native prairie look like?

I recently had the opportunity to visit some of Canada’s great native prairie grasslands in the southwestern corner of Saskatchewan, to help out with the Breeding Bird Atlas of Saskatchewan. The photo below givens an indication of what our native Mixed Grass Prairie looks like.

Threats to Mixed Grass Prairie Grasslands

The remaining intact Mixed Grass Prairie habitat generally has lower soil quality and receives lower amounts of annual precipitation than other regions of the prairie, but the threat of the plough remains, primarily due to the influence of high crop prices on landowner decision making and government policies related to the management and retention of crown grasslands.

In addition to the loss of this habitat, degradation of habitat quality has occurred. The Ecosystem Status and Trend Report of 2010 states that “about 8% of the native rangelands and tame pastures assessed in Alberta and Saskatchewan were considered ‘unhealthy’ as a result of overgrazing and invasion by non‐native plants.”

Despite habitat loss, opportunities exist to conserve and restore remaining large areas of the Mixed Grass Prairie.

Why should native prairie be protected?

Canada’s native prairie grasslands are part of our home and native land. This habitat, with its dry grasses waving in the prairie wind, carries visions of the millions of thundering hooves of the Plains Bison that once roamed across the Great Plains of North America. It is a landscape resilient to extremes of drought and cold. It is unique. It is an important element of our natural heritage. It is to be celebrated and revered. Burrowing owl, black footed ferret, black tailed prairie dog and many other species depend on grasslands for survival. The grasslands depend on you for protection.

2 comments

Thank you! The world need more information on the consequences of our modern mismanagement, and the possibilities in a holistic approacch.

Great content! Great opportunity!!!!!