It’s hard being a bat these days.

Bats have had a bad reputation for centuries due to unfounded fears, most recently getting bad press with the global pandemic. Also, in the last decade, many continue to face the threat of White-nose Syndrome (WNS) that’s wiping out millions of bats in North America. There’s also habitat loss to contend with, declines in insect populations (Canadian bats’ food source) largely due to pesticide use and massive wind turbines to navigate.

Some bats persevere. If they are lucky, a few manage to survive the massive die off from WNS that killed thousands of others in their colony while hibernating. Of these, a few might settle into a summer home in a spacious attic. But hopes to rebuild a decimated population lie in the few remaining females of reproductive age that can only give birth to a single pup a year.

Still, these bats offer some optimism. Research is uncovering that some bats that survive the winter are showing signs of resistance to WNS. Therefore, these remaining bats are a key to the future of these animals in Canada.

The Unwanted Guest

The struggle doesn’t always end there. Even though bats don’t generally pose a problem for the home, when an owner finds out about their guests, the bats are often evicted. Typically this is done very humanely, using a one-way door that lets them leave but does not give them the ability to get back in.

But eviction doesn’t have to always be the answer. Bats can make pretty good neighbours – they’re quiet, don’t chew through wires or walls the way mice do and they help control the mosquito population for us. An ideal situation for the bats is to leave them there or build an interior wall to keep the house guests to a certain section of the attic, along with a drop sheet to catch any guano (bat droppings) that might build up.

Understanding Evicted Bat Behaviour

While an eviction isn’t thought to directly harm the bat, it’s not well known what actually happens to them. Are they able to find a new home? Do they stay nearby? Do they use a bat box if one is put up nearby? Do these bats end up surviving at all?

To answer these critical questions, we sought out a colony of Little Brown Myotis (the species hardest hit by WNS and known to use buildings as roost sites), living at a site where the owner was already planning a humane eviction. The site turned out to be sites (plural) with bats roosting in several spots of a rustic but well maintained cottage property — three main buildings and two sheds.

During the summer of 2021, we aimed to catch and release these bats, having secured the necessary permits, the help of bat expert Derek Morningstar and two participants from the Canadian Conservation Corps program. We planned to catch bats as they emerged from their roost and outfit several of them with small radio transmitters to be able to track them after eviction. These are small devices (about the size of a watch battery) and adhered to established protocols to ensure they don’t impede the bats in any way.

Tagging Bats

We managed to attach seven radio transmitters to Little Brown Myotis and one on a Big Brown Bat for comparison (Big Brown Bats will roost in the same areas but are much less susceptible to WNS). The tags were affixed to each bat using surgical glue, which falls off after two to three weeks. They were all checked for health, weight and a swab was taken to send for testing for the presence of WNS. The bats were released immediately afterwards to continue their nightly foraging. All the bats we received results for tested negative, which was a great sign.

Tracking Bats Using Radio Telemetry

At this point, the eviction had not happened yet. The bats were able to return to their roost so we could see what they do under normal circumstances. We also wanted to find exactly where they were staying. Radio telemetry is a common way to track all sorts of wildlife. A VHF antenna, like a small version of the old antennas that would be seen on people’s homes, is attached to a receiver that is tuned to pick up the frequency of the individual transmitter.

When we got close enough and were able to point in the right direction, we could hear the clicking of the transmitter to pinpoint the location – the closer we were, the louder the sound was. To help with this, we worked with the Species at Risk Program of the Shawanaga First Nation, which has carried out bat tracking projects in the area and has a knowledge of the local landscape. This has the makings of a great partnership going forward as our interests align to conserve bats and other at-risk species.

After three days of tracking and finding the bats moving around within the buildings – some returning to the same spot at the end of each night, some moving to different spots in the buildings – the eviction was about to take place. There were a lot of spaces for the bats to go and they were resourceful, many finding new spots within the buildings that the eviction overlooked. The next day, we attempted to evict bats in the remaining site areas. We also installed three different styles of bat houses to provide a new home and test whether bats preferred a certain design over others. These were in addition to the five bat houses the owner already had installed in previous years. The owner was outstanding, already understanding the benefits of bats and wanting to help provide habitat for them (just not necessarily in the buildings).

Now for the interesting part. What happened to the bats when they couldn’t get back in? I woke up early the next morning to watch the commotion. Bats were flying about, wildly searching for ways back in; landing on the walls and ducking up under the eaves. I couldn’t help but feel badly for these bats who were just looking to get back to their roost, couldn’t understand what changed from the night before and why they were unable to get back in. Then at 6:15 am, they all disappeared, almost in unison and all was quiet.

This was the same trend the next morning. They must have realized that day was coming so left to head to other, known roosting areas nearby. Our tracking revealed that two managed to foil the eviction and moved to new areas in the soffit. Luckily, this area was not within the building so it was alright to leave them there.

Over the course of the next two weeks, the bats led us through forest, over lakes, down ATV trails and to cottages and the nearby town as we followed their daily movements. We were tracking during the day, meaning the places we located the bats were their roost sites and where they ended their activities the night before. These stayed relatively consistent for many of the bats, returning to the same new site they found after leaving the cottage.

One stuck to the forest, two kilometres away, moving from one tree to another but generally in the same area; another moved to an empty neighbouring cottage, then to a house in town, then a nearby tree and back to the empty cottage. One left the first night after our capture and went out of range of our 10 km search area or deep into the forest where we weren’t able to pick up its trace. After the eviction, two others followed suit and we never found them again.

The entire crew was glad to see the bats were active and all seemed to find new areas to roost. We can’t say for certain about the bats that headed out of range, but given the time of year, they likely headed out to swarming sites, which are areas bats congregate in the late summer to mate before moving into their hibernation sites. These can be dozens of kilometres away from their summer roosts, so it’s not surprising that we could have lost the trail.

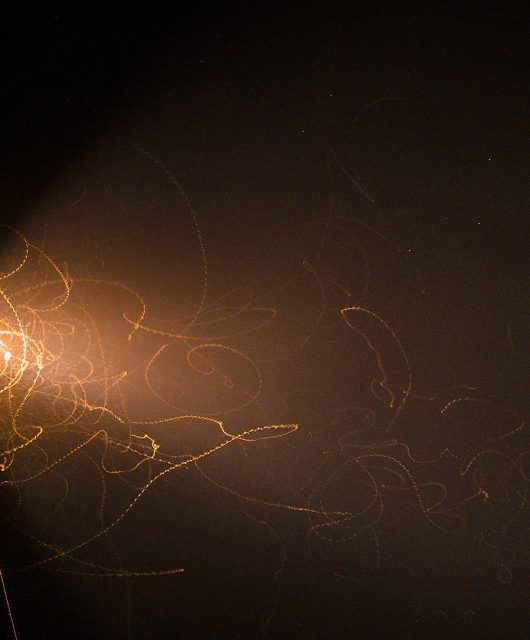

We tracked the bats over the course of several nights and were able to confirm the bats were indeed moving around. This diminished our fears that they might be in the same roosting site day after day because they hadn’t survived. And sure enough, we picked up several of our tagged bats flying overhead as they ducked in and out of view all the while hearing through the receiver that they were just above us.

Conclusions

We’re still in the process of analyzing the movement patterns of the tagged bats to really understand what the impact of an eviction is, but at first glance these bats seemed able to find new homes.

As for the bat houses, they did end up being homes to several bats. Every day there seemed to be a couple more bats in the bat houses and by the end of the three weeks, 10 bats were using these. None were the bats that we had put transmitters on, but there were more in the buildings than we had caught and outfitted with these. Generally, there didn’t seem to be a preference for one design over another. It will certainly be interesting to head back next summer to check in on our bats and see what they’re up to.

2 comments

Great article. We can provide urban roost sites if ever interested in expanding the study.

Bill Dowd

Skedaddle Humane Wildlife Control

President /CEO

This is the type of evidence-driven research that really complements people’s desire to help! Well done! And kudos to the property owner.