Many of Canada’s lakes, streams and rivers are part of ancient migratory routes that have been travelled by aquatic species for thousands of years.

At various stages of life, salmon, sturgeon, American Eel and many other species have evolved to use different parts of these systems to hatch, mature, and breed. Over time, the construction of road culverts, dams, and other structures has created barriers to animals swimming these ancient routes. In many places, fish can no longer pass from one important habitat to another. This loss of passage has been a major factor in the decline and disappearance of many species.

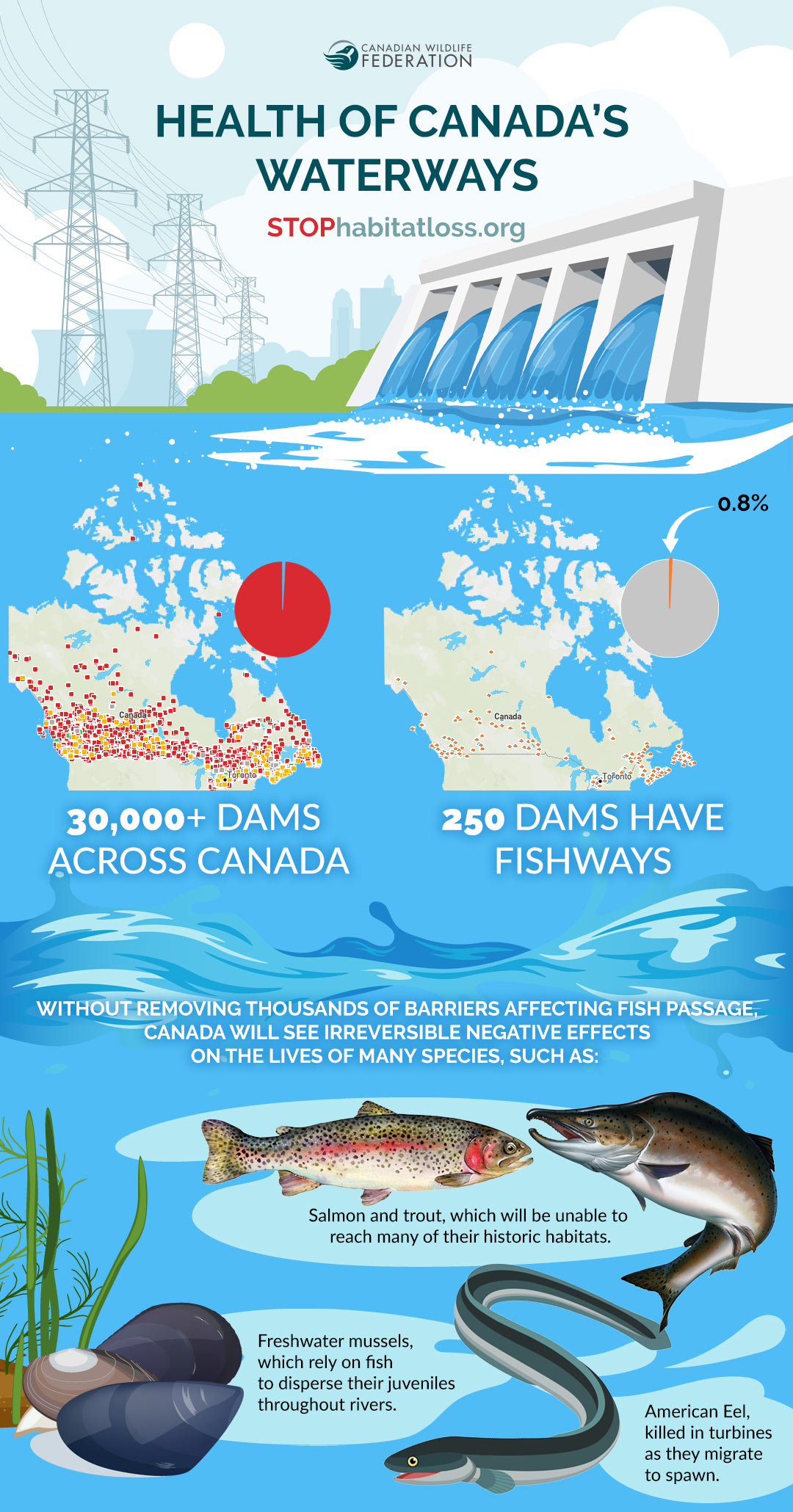

The Canadian Wildlife Federation (CWF) is actively tracking and mapping aquatic barriers through the Canadian Aquatic Barriers Database (CABD). What we’ve learned so far tells a damming story about the health of Canada’s waterways. For example, while there are over 30,000 dams across Canada, only 250 are currently known to have fishways that provide upstream passage for aquatic species. While some rivers and streams have many kilometres of unobstructed flow, others have so many barriers they are simply unavailable to many species.

The good news is that many of these aquatic barriers can be fixed or decommissioned. Other measures can be taken to ensure safe passage around them. The United States is meeting this challenge head on by funding and implementing programs that have seen 800 dams removed in the past 10 years. Similarly, within the European Union in 2022 there were 325 river barriers removed, including several hydro-electric dams. Closer to home, in British Columbia, CWF is working with multiple partners to restore hundreds of kilometers of fish passage throughout the province. In the past five years, this work has restored access to more than 3.3 million square metres of habitat (328 hectares) at 25 sites throughout British Columbia.

On a national scale, however, Canada has fallen behind. A lack of federal funding and coordination on this issue means further endangerment of our nation’s freshwater species.

Why is This Important?

Many species are at risk or in decline because of aquatic barriers

Barriers along aquatic migration routes have resulted in the loss and decline of many fish species. These losses can be devastating to Indigenous communities. They also affect Canada’s tourism and fishing industries, and further entrench our nation in the global biodiversity crisis. Many other wildlife species, like Orcs, eagles and bears, depend on healthy fish populations to survive. Here are some examples of species that have been affected by aquatic barriers:

Lake Sturgeon in the Great Lakes

The ancestors of modern Lake Sturgeon shared this planet with the dinosaurs and have survived many changes on Earth. However, though they have made a living in the cold, fresh waters of North American for millions of years, Lake Sturgeon are now a species at risk in Canada. In the Great Lakes area, aquatic barriers like dams interrupt the fishes’ upstream migrations to breed. The flow and temperature of streams and rivers has also been altered by the construction of these barriers. Though efforts are being made to improve water quality and regulate fishing to help Lake Sturgeon populations recover, aquatic barriers that support pulp and paper mills and hydropower dams continue to be major threats to their recovery.

Pacific Salmon

Like Arctic Caribou and Monarch Butterflies, Pacific salmon are some of the world’s great migrators. Their journey begins with a swim to the water’s surface for a sip of air to fill their swim bladders after they hatch. As they mature, they continue over sometimes hundreds or even thousands of kilometres from their freshwater homes to the ocean, and back again to breed. There are tens of thousands of aquatic barriers in salmon-bearing streams in British Columbia. With many populations already at risk, reclaiming whatever habitat possible is critical to their survival.

Atlantic Salmon from Lake Ontario

As glaciers retreated at the end of the last ice age, Atlantic Salmon colonized Lake Ontario from the ocean and evolved into the largest entirely freshwater population in the world. Early explorers in the 1600s wrote that every stream, creek and river connected to the lake teemed with salmon. Over time, development, agricultural expansion, various industries, and overfishing led to the disappearance of this unique population from Lake Ontario. Hydroelectric dams and aquatic barriers associated with pulp and paper mills were a major contributing factor in this decline and continue to be the single greatest impediment as efforts are made to recover the species.

We CAN Reverse Some of the Damage

Many aquatic barriers are no longer serving the purpose for which they were originally designed. Some have fallen into disrepair, while others, like some dams, are reaching the end of their functional lives. Many countries are investing in programs to map, remove and repair barriers, restoring fish passage for millions of fish and helping recover diminished and lost populations. In the United States and European Nations, exciting progress is being made to reconnect aquatic habitat:

Populations of Migratory River Herring Return to the Millions in Maine, USA

There are 581 active dams in Maine, 39 per cent of which are used for hydroelectric power generation. These dams are significant barriers to fish passage, and along with other factors have led to serious declines in fish populations. In answer, the Penobscot River Restoration Project was undertaken to restore fish passage on the Penobscot River and some of its tributaries. Two major dams have been removed through the project, a fish lift has been installed on a third dam, and a fish bypass constructed around a fourth dam. Following removal of the first dam in 2014, numbers of migratory River Herring grew from only several hundred individuals to over 180,000 individuals the following year. By 2018, the numbers had reached 2.3 million.

European Countries Remove Record Number of Dams in 2022

In 2022, European Nations demolished a record number of aquatic barriers and opened hundreds of kilometres of fish passage. Norway blew up the 106-year-old Tromsa River hydropower dam and replaced it with a more natural step-pool system, connecting habitat for Grayling, Burbot, Alpine bullhead, Eurasian Minnow and Brown Trout. Meanwhile in France, the La Roche-qui-boit hydroelectric dam was demolished, following the removal of the Vezins dam in 2020. As a result, the Sélune River in Normandy is now returned to a free-flowing state for Atlantic Salmon, Sea Lamprey and European Eel.

And in Ukraine, despite the on-going war, the 120-year-old Bayurivka Dam was removed, opening 27 kilometres on the Perkalaba River and allowing endangered fish species like the Ukrainian Danube Salmon and Ukrainian Brook Lamprey to reach their ancestral spawning grounds. The move brings Ukraine a step closer to restoring 3,000 kilometres of free-flowing rivers by 2030. In 2023, barriers were removed in 15 different E.U. countries, and the removal of 166 of these barriers alone led to over 4,300 kilometres of river being reconnected.

This is an Opportunity For Reconciliation

Indigenous Peoples have relied on fish for food for millennia and have strong cultural ties with many aquatic species. Supporting efforts by Indigenous organizations to recover fish populations is an important step in reconciliation. Many Indigenous Nations are already leading the way. The Colville Confederation Tribes and the Okanagan Nation Alliance, for example, have worked for 20 years to bring Sockeye Salmon back to the Okanagan Basin. Their efforts to restore fish passage have led to record salmon returns, with the number of Sockeye counted jumping from under 100,000 in the early 2000’s to over 650,000 in 2022. The success of this work has paved the way for a parallel program in the upper Columbia River. Meanwhile, Lake Babine Nation has been working ensure free and clear passage to one of many streams that are critical to salmon migration early in the season. After restoring fish passage on Cross Creek in 2021, the number of salmon counted upstream of the previous barrier jumped from 127 to 917.

1 comment

Good morning, I’m with the Port Colborne Optimist Club and we are having our annual kids fishing derby on Father’s day. Do you have any educational pamphlets or papers on fish in our lakes or water conservation?