Did you know that insect pollinators generate one out of every three bites of food we eat?

Or that their worldwide economic value has been estimated at $229 billion CAD per year? Pollinators are critical to the health of our environment, our economy and ourselves.

We rely on the honeybee, which is not native, for much of the pollination of agricultural crops, but parasites and disease are making honeybees less reliable. In Canada there are thousands of species of native pollinators – including bees, flies, wasps, moths, butterflies and beetles – that help to pollinate crops and are responsible for pollinating almost all of the flowers in our forests, fields and tundra. But even our native pollinators are in trouble, and their global populations are declining due to habitat loss, pesticide use, climate change and disease.

To reverse the trend, we need to boost native (or wild) pollinator populations in two key ways – abundance and diversity. How can we do this? One way is to understand how Canadian farmers can support wild pollinators. Agricultural land – including woodlots, hedgerows and grassy field margins – provides pollinators with important food and nesting sites. This means restoring natural habitat on farms may be essential to maintain pollination services.

Unfortunately, little research has been done to understand how different habitat types impact pollinators in terms of abundance and diversity. That’s where the Norfolk County Pollinator Project comes in! By working collaboratively with farmers, the goal is to understand how to manage farmland to contribute both to sustainable agriculture and to healthy pollinator populations.

How does the project work?

The Norfolk County Pollinator Project is a collaborative study between Dr. Carolyn Callaghan, Senior Conservation Biologist at Canadian Wildlife Federation; Dr. Jeff Skevington, a world-renowned entomologist with Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada; Dr. Nigel Raine, University of Guelph Professor and Rebanks Family Chair in Pollinator Conservation; along with participating farmers in Ontario’s Norfolk County.

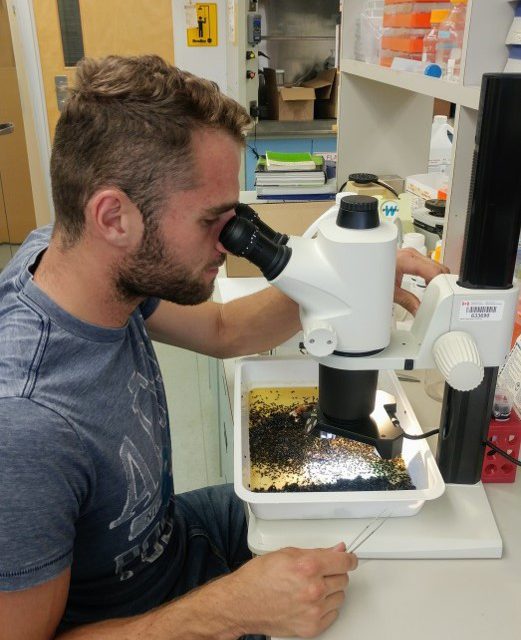

To sample pollinator populations, thirty Malaise traps—large, tent-like structures designed to collect insects—were set in three different types of natural habitat on participating farms. They were emptied twice weekly throughout the summer of 2018, and CWF students then sorted through jars with thousands of insects to separate the bees and fly pollinators from other insects. The pollinators were then dried and pinned in summer 2019 and are now being identified and labelled at the species level. This process is painstaking and time-consuming, but it’s necessary to ensure the accuracy of the data.

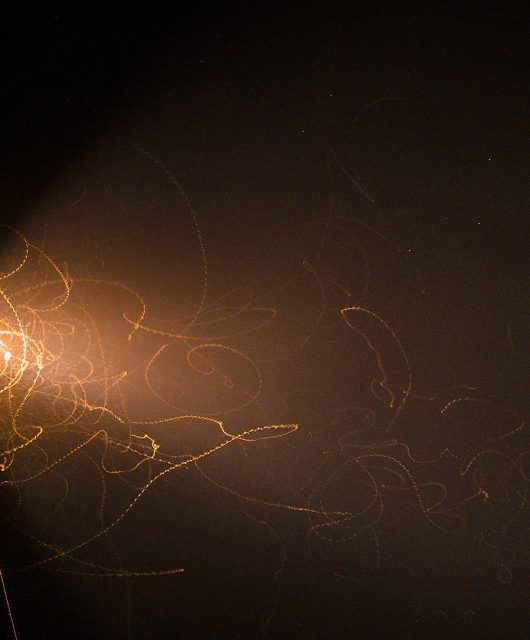

To help automate and confirm species identifications, our collaborators at Agriculture and Agri-Food Canada are continuously developing a Next-generation DNA sequencing system: DNA barcoding.

What is DNA barcoding?

DNA barcoding is an exciting avenue of research that ensures the accuracy of the data collected during the Norfolk County Pollinator Project. It analyzes the DNA of insect specimens that are difficult or impossible to identify by visual characteristics to make a precise species identification.

How does this work? If the species of a specimen can’t be determined by sight, then a short fragment of its DNA is sequenced to identify its building blocks, or DNA barcode. This is then compared to the DNA barcode of known specimens in a reference library. When the DNA of the sample matches the DNA of a known species, the specimen is accurately identified, and the validity of the data is ensured.

How is the project progressing?

Data from the first field season is currently being processed and added to the Canadian National Collection database for statistical analysis. Samm Reynolds is our new graduate student who will be diligently collecting and analyzing data. Khorshid Ghahari is our technician who has pinned and labelled the many thousands of samples.

Data from the first field season is currently being processed and added to the Canadian National Collection database for statistical analysis. Samm Reynolds is our new graduate student who will be diligently collecting and analyzing data. Khorshid Ghahari is our technician who has pinned and labelled the many thousands of samples.

In 2021, a second field season will be carried out. Its data will be processed using the same methods, including DNA barcoding, and added to the database. When the data from both seasons have been processed, a report of the findings will be published. The results are intended to inform government policy and help Canadian farmers support our all-important wild pollinators.

If you want to learn more about how you can help pollinators, visit HelpThePollinators.ca.

Contributor: Samm Reynolds, CWF Pollinator Field Technician

3 comments