Cavities in snags and hollow trees provide essential habitat to countless bird, mammal and insect species. When cities take these trees down, usually to avoid legal liability, local wildlife disappears.

Right outside my window, in the park across the street from my downtown Toronto house, a dramatic rescue is underway. A hard-hatted worker bobs about on a truck’s aerial platform amid the upper branches of a massive old oak that has seen better days. She moves about the canopy with a chainsaw, slicing off leafless branches, ragged snags and even a couple of sizable limbs. The end result will be an ancient, somewhat goofy-looking three-fifths tree that can live on a little longer.

As importantly, at least to the city’s legal department, it won’t be a threat to anyone. It turns out that’s the point of most tree pruning that happens in towns and cities. It is not about the trees’ health or even about esthetics. It is motivated by the municipality’s legal obligation to keep dwellers safe by preventing deadwood from dropping on their heads.

In the category of unintended consequences, the effect of this constant trimming has been a decline in urban biodiversity. That’s because the tiny cavities that form in cracked, broken or dead limbs and throughout dying, hollowing trees at risk of falling are crucial to the survival of a wide range of creatures. Remove deadwood and you are creating a housing crisis for at least 89 disparate species of birds, mammals and insects in Canada that rely on it for nesting, roosting, breeding and food storage. Worse, in many species, the number of birds actually breeding is determined by the availability of tree cavities. This is at least part of the reason some woodpecker populations in Canada have dropped precipitously.

Natural cavities result from branch breaks and cracks. They form too in old cankers and wounds that long ago compromised bark coverage. Fungus intrudes and spreads; over time it causes rot and invites insects. As the heartwood softens and weakens, woodpeckers like the northern flicker (Colaptes auratus) and the yellowbellied sapsucker (Sphyrapicus varius) move in, looking either for bugs to eat or to carve out a secure nest, or both. Then they move on. Pileated woodpeckers (Dryocopus pileatus), the giants of the grouping, leave a particularly roomy space when they decamp. Lesser excavators like the red-breasted nuthatch (Sitta canadensis) and blackcapped chickadee (Poecile atricapillus) join in, modifying and adapting old cavities for their purposes. Others that are unable to dig or chip away, like tree swallows, wrens and bluebirds, simply move in, bringing in a few elements, bits of moss, twigs — the little things that make a house into a home, a hole into a nest. Competition can be intense: protected from the elements and easily defended, larger cavities are hugely attractive, and not just for birds.

These cavities are essential to the survival of tree squirrels (naturally), as well as porcupines, raccoons and other mammals common in your city. Those that can gnaw on the softened wood to modify it to their needs, but the needle-like teeth of many predatory mammals mean they cannot and must settle into whatever suitable cavity they can find. In the woods, it is a simple task; hollow trees abound, along with countless snags. As one survey found, cavities in Canada’s forests last 14 years on average. But in many Canadian cities, local wildlife are lucky if cavities are still available after 14 weeks.

This is urban wildlife’s housing crisis: a single hollow tree left standing is like a multistorey apartment complex for a diverse residential mix, offering years of safe and biologically “affordable” housing to the most vulnerable. And cities are tearing them down. What’s more, according to one study from the University of British Columbia, woodpeckers are responsible for up to 99 per cent of excavated cavities in Canada, yet these would-be builders are in decline. Most Canadian cities have a sizable parks and forestry maintenance budget and a mandate to keep planting more trees. At a time when conserving biodiversity is a crucial response to the climate crisis, can city foresters — and their risk-averse legal colleagues — find a way to keep dead but extremely lively trees standing? If not, someone needs to figure out a way to replace the essential habitats they are destroying.

Learn more about our feathered friends at WildAboutBirds.ca

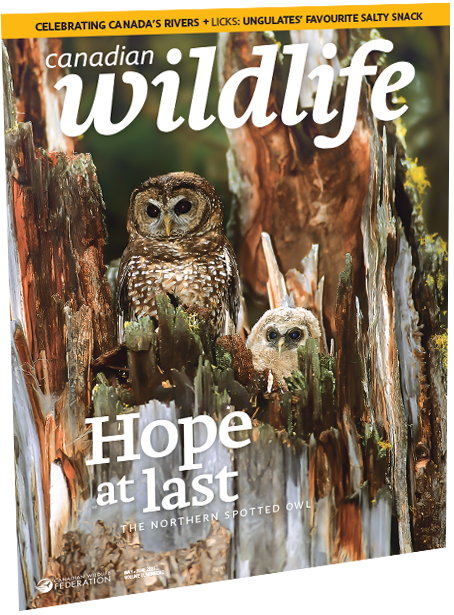

Reprinted from Canadian Wildlife magazine. Get more information or subscribe now! Now on newsstands! Or, get your digital edition today!

1 comment

Though a degree for the field is not always required, arborists still have to go through intense training and earn certain certifications before pursuing the position. This education often helps them perform their job duties more effectively and ensures they maintain a safe work environment.