In nature, body size plays an important role in different life stages, such as growth and reproduction and can impact species recovery.

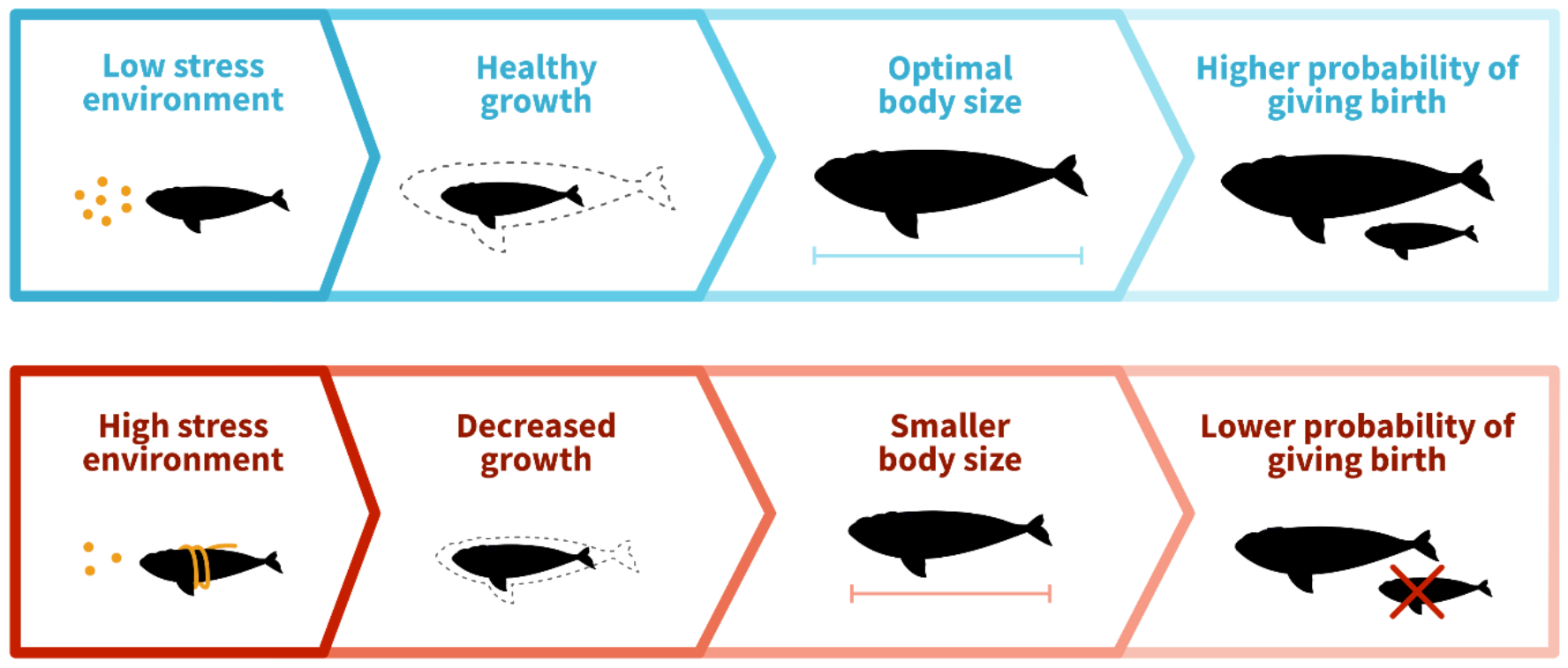

A smaller body size compared to the full potential size (called the asymptotic size) can mean that the animal is unhealthy and might be slower to reach sexual maturity, require more time in between births, or even affect the size of their offspring. Animals, especially young ones, allocate energy gained from feeding into their growth. But when they are exposed to stressful environments, such as through changes in their habitat or human activity, growth can be negatively impacted.

Such impacts were seen in a recent research study that found that smaller breeding female North Atlantic Right Whales have a lower chance of bringing a pregnancy to term.

Back in 2020, a study used drone images to compare North Atlantic Right Whale body size with that of their cousins, the Southern Atlantic Right Whales in Australia, Argentina and New Zealand. They found that juvenile and adult North Atlantic Right Whales were, on average, smaller than the Southern Atlantic Right Whale populations.

North Atlantic Right Whales Smaller Due Mostly to Climate Change

The difference between the northern and southern populations was attributed to the level of exposure to human activities: climate change. The main food of North Atlantic Right Whale, a copepod called Calanus, has shifted northward in the last ten years due to climate change. This has led North Atlantic Right Whale to follow their food to summer grounds in the Gulf of St Lawrence, where they need to transit through intense fishing areas and some of the busiest shipping corridors of the world.

Not only do North Atlantic Right Whales not grow as big anymore, but this recent study also found that smaller body sizes were associated with lower calving probability. For example, an 11-metre long female North Atlantic Right Whale has a 14 per cent chance of successfully giving birth on a breeding year, compared to 56 per cent chance for a 14 metre female. Female right whales usually have a three-year breeding cycle: one year for the gestation, one for nursing her calf and one for rest. This means that due to all the human-caused impacts affecting individual whales, it takes more time for a female to gain enough energy to fully support a complete reproductive cycle.

Since 2015, North Atlantic Right Whale females need at least seven years between births. We are still unsure at which point in the reproductive process the pregnancy fails, but scientists think that this relationship explains the observed long-term decline of North Atlantic Right Whale calves each year.

For a critically endangered species, every new calf is vital for the survival of the population. Currently, there are an estimated 70 breeding females in the North Atlantic Right Whale population of 356 whales. So far in 2024, we have observed 19 new calves, which is the highest reported number of calves since 2013!

While conservation efforts and management measures are rightfully targeting the reduction in North Atlantic Right Whale mortalities (i.e., reducing the rate of entanglements and vessel strikes), we also need to consider increasing the population numbers with healthy whales. Canada’s action plan for the recovery of the North Atlantic Right Whale population is to see an increasing population trend over three generations, which is about 60 years. If we hope to see this population recover, management actions should not only focus on reducing mortality, but also aim at protecting and enhancing female growth and health.