The American Eel — known as kichisippi pimisi in Algonquin and tyawerón:ko in Mohawk — is an incredibly important species not only ecologically but also culturally.

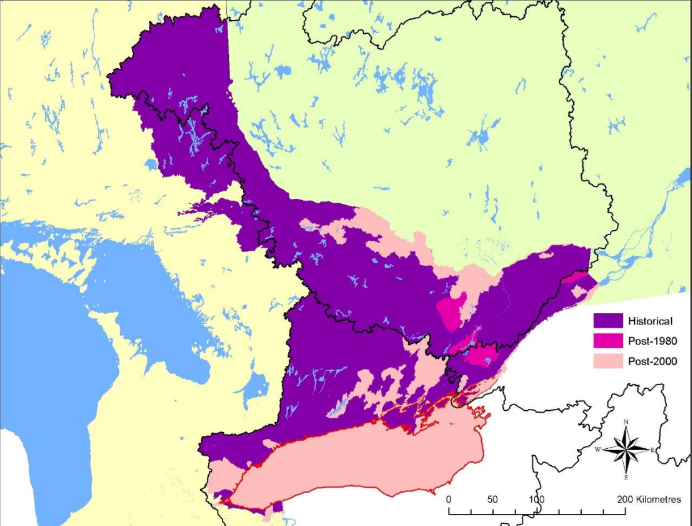

They have been in decline for decades, with some populations having declined by as much as 99 per cent. The American Eel’s life cycle is very unique. They live throughout rivers and waterways along the eastern coast of North America. When they reach their mature stage (which may take between 10 to 25 years), they migrate en mass downstream to one area of the Atlantic Ocean.

Why Have American Eels Declined So Drastically?

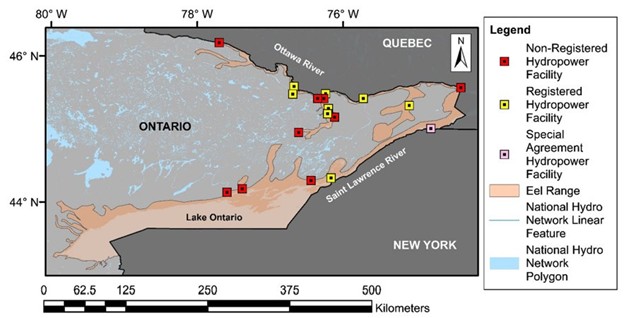

While American Eels face challenges such as poaching, invasive species and habitat loss throughout their life cycles, barriers are the primary threat. This is due to the fact American Eels must migrate between marine and freshwater habitats to complete their life cycles. They face particular risks from hydroelectric dams during their final downstream migration because between 20 per cent and 50 per cent are killed as they pass through the turbines.

Though American Eels need protection throughout their range, the Great Lakes and Upper St. Lawrence population — which is 100 per cent female by nature — is particularly important. This essential population once contributed between one-quarter to two-thirds of the eggs to the global population, which converges to spawn together in the ocean.

Importance to Indigenous Peoples

Many of the Indigenous Peoples in Eastern Canada have a close bond to the American Eel. Eels have been an important source of food, medicine and material to make tools such as snowshoes and is also a cultural symbol. It was historically one of the most important and common near-shore fisheries and a significant part of life and culture.

The steep decline in American Eel populations have been particularly hard felt by Indigenous Peoples. In particular, the Algonquin and Mohawk Nations along the upper St Lawrence and Ottawa River have been leading the calls for better protection for eel along their migration routes.

Damming Evidence

There are more than 4,000 dams in the historic range of the American Eel in Ontario and Quebec. This includes more than 200 hydroelectric dams as well as other blockages, such as culverts where roads cross streams. Some of Canada’s largest dams in the Upper St Lawrence system — including the Saunders Generating Station in Ontario and the Carillion Generating Station in Quebec — are in the beginning stages of generational refurbishment projects.

Though efforts have been made to improve upstream passage at the Saunders Generating station, the same cannot be said for safe downstream passage.

Looking Towards Indigenous Peoples

There are emerging technologies, strategies and practices — many of which are based on Indigenous Knowledge — that could improve safe eel passage while not significantly affecting power generation.

The Fisheries Act requires consultation with Indigenous stakeholders as part of the authorization process and enshrines respect for and inclusion of Indigenous Knowledge in this process. For any decision that affects Indigenous rights the department of Fisheries and Oceans is required to consider any adverse effects on these rights, and has a duty to consult. This includes approval of projects that cause the death of fish or the harmful alteration or destruction of fish habitat.

Indigenous Nations have the greatest potential to meaningfully influence eel conservation due to their constitutional rights, centuries of Indigenous Knowledge and their extraordinarily strong cultural connections to the American Eel. It is imperative that hydroelectric providers consult with Indigenous Peoples and consider their knowledge in the refurbishments.

The Canadian Wildlife Federation, headquartered in Kanata on the traditional territory of the Algonquin Anishnaabeg people, has spent years working with partners to support better outcomes for the American Eel and increase public awareness. We will continue to work with a broad coalition of conservationists including Indigenous partners to achieve these goals.