This is part one of a three-part series on the Monarch Butterfly Recovery written by the Canadian Wildlife Federation’s Senior Terrestrial Biologist Carolyn Callaghan.

As I write this blog, I am flying over the route of the eastern Monarch Butterfly’s migratory journey.

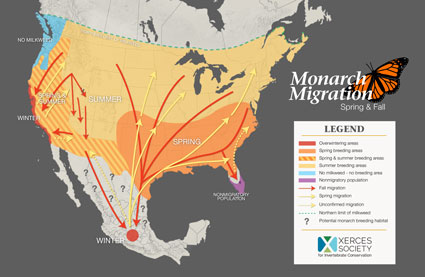

Millions of these iconic butterflies make this flight in March, from Mexico to the southern United States, to begin a new generation by laying their eggs on milkweed.

Unlike the Monarchs, I have it easy.

I am sitting on an Airbus A320 airliner, with a 37.6 metre wingspan to jet me the 4,291 kilometres home. I do not weigh half of a gram nor do I have a 10 centimetre wingspan that I must steadily flap in order to make it northward across mountains, plains, busy roadways and agricultural fields. I do not have to endure extreme weather events including temperatures too hot or cold, too rainy or windy. And the northward migrating Monarchs do this after having already migrated up to 4,500 kilometres from either southern Canada, northern or mid-western U.S. last fall. It is the same generation that flies from the northern breeding range in the fall to the overwintering grounds in the Oyamel Fir highlands south of Mexico City, then northward to the southern US in late winter. This super generation’s grandchildren and great-grandchildren will continue northward in successive generations to eventually arrive in Canada in May.

Let me tell you why I am currently in an airplane thinking about Monarch Butterflies. I am returning from an awe-inspiring three-day “meeting of the minds” with the goal of Monarch Butterfly recovery. The government of Mexico hosted a meeting of scientists from Canada, US, and Mexico to discuss threats to the Monarch population, review the science of the species and its phenomenal migration and discuss the next steps to reverse the decline that has been evident for decades.

An International Species That Needs an International Solution

This is not the first time this science committee has met. Since 2015, the committee has been identifying knowledge gaps, implementing science to fill these gaps, sharing data, collaborating on projects, and encouraging each other to work harder for the conservation of this species. A tri-national agreement to work together to conserve this Endangered species, enacted by the presidents of Mexico and the U.S., and the prime minister of Canada in 2014, was the impetus for initiating the tri-national science committee. And it was the data and modelling of some of the same scientists on the committee — as well as other scientists that raised the clarion call — that resulted in the tri-national agreement. This tri-national commitment is real, and I can report that significant progress has been made in generating knowledge and taking conservation action to reverse the population decline. And all scientists and land managers at the meeting agreed that much more needs to be done to stem the tide of decline.

New Canadian Federal Status: Endangered

The population decline is why the Canadian government listed the Monarch as Endangered in December 2023. The work has already begun by Environment and Climate Change Canada’s Monarch recovery team to build a recovery strategy, which is due in December 2024. The recovery strategy will be a roadmap for reversing the decline and will be followed by an action plan that will guide actions and timelines for conservation outcomes. This is a significant commitment by the government of Canada, and the recovery strategy will no doubt be a guiding light for all of society to help with recovery efforts. Indeed, it will take that to successfully recover the Monarch.

The primary threats to the eastern population of the Monarch Butterfly include habitat loss, broad-scale pesticide use and climate change. All three are pressing down on the Monarch, resulting in a lower population that fluctuates from year to year but seems to have difficulty reaching and sustaining the six-hectare target area of the overwintering population. Because it is virtually impossible to count individual Monarchs on the Oyamel Fir trees, teams of dedicated conservationists measure the area that is occupied by the overwintering population. The butterflies cluster together on roosting fir trees across several reserves. The total of this area is reported at this time each year and we wait with bated breath to learn the size of the area occupied by Monarch. It is members of the tri-national science group that determined, through population extinction modelling, that six hectares is the target size that will keep the migrating eastern Monarch population from extinction.

A Critical Drop: The overwintering area for Monarchs in 2023/24 decreased 59 per cent since last year’s overwintering area.

It is with more than a hint of despair that we learned on February 8, 2024 that the area in winter 2023/24 totaled only 0.9 hectares. This is the second lowest area reported since the annual counts began in 1993/94 and represents a decrease of more than 59 per cent over last year’s overwintering area.

Is it time to throw in the towel on Monarch; to walk away and admit defeat? Not at all! With a tri-national commitment to recovery and actions on the part of the three governments and civil society, members of the scientific committee expressed confidence that the recovery of the Monarch is within reach. A united front will be needed, and you can help.

1 comment

It ocurred to me in the 1st paragraph that you were missing one thing. Flying. Airplanes leave the most air pollution than any other vehicular and it goes straight down the west coast to Mexico. Everyday, any times of day they spread volumes of jet fuel waste in the air and over the land. Have you ever had a blast of that exhaust in your face? It sticks to you and makes me nauseous and head aching. So. Flying is a deadly plague on our planet. One that needs pushing to creat clean fuel. Wil their ever be such a thing. Humans are eating up the planet like yeast in a petri dish.

Susan Collacott