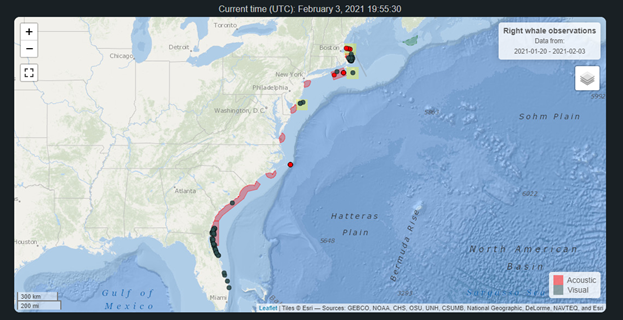

The warm, shallow waters off northern Florida, Georgia and North and South Carolina is where Right Whale females go.

They’ll head south at the end of a year-long pregnancy to give birth and nurse their single offspring. A few months later, mother and calf begin their long journeys north along the eastern seaboard (among the busiest coastlines in the world) to northern feeding grounds in cooler Canadian waters.

Right Whales can begin calving at age six, though the first calf, delivered after a year-long pregnancy, is often delayed to about age 10. They can then continue to give birth throughout their lives (a natural lifespan is close to 100 years, though the average age at death is less than half that, largely due to human activity and shifting food resources in a warming ocean.)

Historically, the normal, healthy interval between Right Whale births has been about three years; recent studies show that the time gap is now as long as six to ten years. Research suggests that this is the result of entanglements and other stressors which weaken the whales and reduce their ability to procreate. They need an abundance of nutrients and blubber just to support their gigantic calves, so anything that inhibits their ability to feed or that places extra demands on their energy output is bound to have an effect on their capacity to reproduce and rear their young.

Only half of female Right Whales live to maturity and there are fewer than 90 reproductively active Right Whale females alive today.

Given that since 2017, 34 Right Whales have died as a result of entanglements and collisions (with another 15 badly wounded whales likely to die from their injuries) combined with the stunning fact that 85 per cent of Right Whales show entanglement scars, it is clear that the future of this species hangs in the balance.

It is not an exaggeration to say that when we rescue one female Right Whale, we are rescuing all her future calves, and in very real terms we are rescuing a species one whale at a time. That is why so much effort goes into tracking, monitoring, and rescuing entangled Right Whales. And why more needs to be done.

Case Studies

Snow Cone

/cloudfront-us-east-1.images.arcpublishing.com/tgam/KOEH33WZFBDCJBO3TJEPEFSLKU.jpg)

It was near Cape Cod, Massachusetts in March 2021, that Snow Cone, a 16-year-old breeding female Right Whale, was spotted, entangled in commercial fishing gear. (The nicknames, helpful in keeping track of each whale and for engaging the public are often inspired by their unique markings.) That day, US rescuers were able to free Snow Cone partially from the gear, but some rope remained lodged in her jaw before she dove deep and disappeared from sight.

She was spotted again May 10, 2021, by a Canadian whale surveillance plane near Shippagan, N.B. The next day Canadian rescuers from Campobello Whale Rescue hightailed it to the sight, rescue boat in tow, to attempt to disentangle her again. After getting their specialized craft in the water, they did manage to reach her and succeeded in removing some more of the rope before she fled back into the depths.

Sadly, though hardly atypical, Snow Cone’s first calf, born in 2020, was found dead months later in New Jersey waters, a victim of two violent ship strikes that occurred several weeks apart.

Snow Cone herself was observed in June 2021 but has not been re-sighted since.

Lobster

A Right Whale named “Lobster,” number 3232 in the North Atlantic Right Whale Catalog, and her young calf were sighted in Nova Scotia waters near Brier Island in May 2021. That makes 18 new calves spotted as of early June, the highest number since 2015. Going back a few decades, the average sighting per year was around 23; remarkably, there were only 22 calf sightings in total over the previous four years.

This is thought to be Lobster’s second calf. She birthed her first calf in 2015 at the age of 13. Right Whales are usually detected initially in the southern calving area, but Lobster is among an increasing number first seen with a calf well north of there. The speculation among researchers is that she may also have delivered her second calf in more northern waters. There is considerable debate about whether this represents a northward trend, as we have seen with the feeding zones.

Lobster, named for the callouses on her head that distinctly resemble a lobster with claws, was born in 2002. Frequenting the Bay of Fundy in her first decade, by 2017 she was being regularly sighted in the Gulf of St Lawrence. Interestingly in 2021, she was spotted back in the Bay of Fundy, perhaps en route to the Gulf area.

What YOU Can Do

Sign Our Petition! Support CWF’s Marine Action Plan – MAP is a major conservation plan designed to make Canada’s ocean safer for marine wildlife. We are asking the Canadian government to continue to invest in research and programs that can help us better understand the range and movement of marine mammals. Knowing where these majestic animals are is critical to ensure their survival. Add your voice and help us get the support we need to help protect and conserve marine animals.