Cattle ranchers in the Milk River watershed, Saskatchewan, participated in a federally funded program by taking voluntary actions to support rangeland sustainability, habitat conservation and recovery of species at risk.

In the next 10 to 15 years, many family ranches will pass to the next generation. Ranchers, for good reason, are unwilling to make decisions today that tie their children’s hands in the future. Conservation agreements and easements are popular tools to support ranching families financially while they conserve native grasslands that benefit all Canadians. If we want family ranchers to steward and protect native grasslands, they’ll need Canadians to step up for them as they do for us.

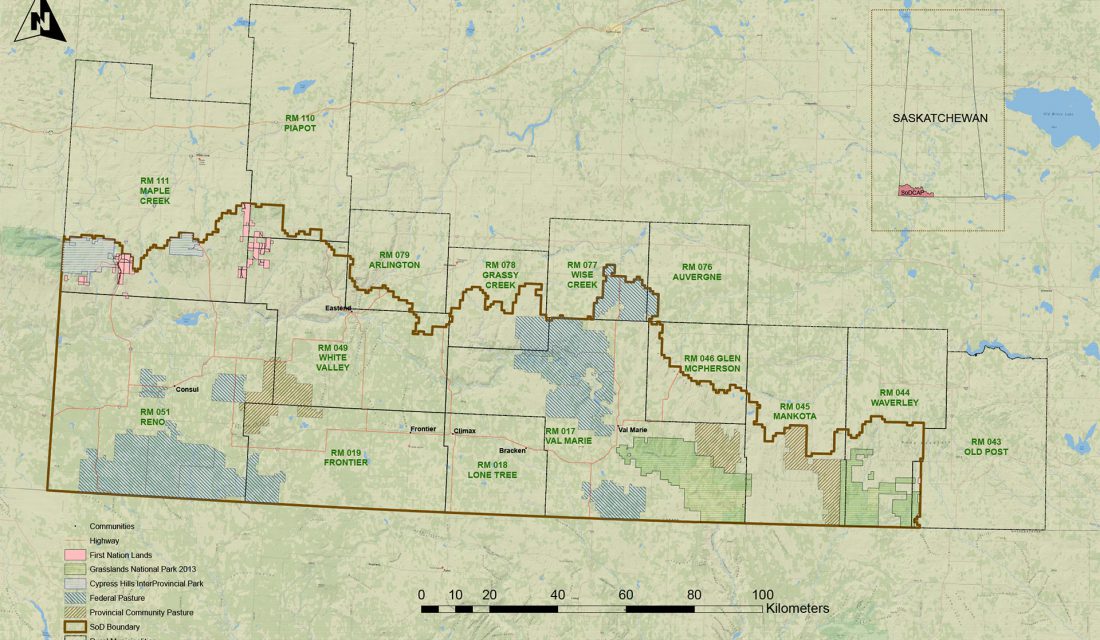

Study Location

The study took place in an area covered by the South of the Divide Conservation Action Program (SODCAP), the organization that helped implement the project locally. Roughly 46 per cent of the land in the study area is privately-owned by about 750 farms. At the time, native prairie provided about 50 per cent of the food for 130,000 cattle.

In Their Words

In 2018, researchers asked 23 participating cattle ranchers to report anonymously how they felt about the program. The results were published in 2021 in the journal Biodiversity and Conservation.

In 2018, researchers asked 23 participating cattle ranchers to report anonymously how they felt about the program. The results were published in 2021 in the journal Biodiversity and Conservation.

Ranchers were satisfied with the program primarily because they could adopt conservation actions that were already working or would work with their operations. They also appreciated the program being implemented by a local organization that they trusted, and that could advise them and provide expertise when needed.

“I think it’s important that the management team are locals and therefore have a better understanding of the landscape they are working on and the attitudes of the producers they are working with.”

Ranchers said that recognition and reward for the conservation actions they take on their land is important to them. They want the public to better understand the role they are trying to play in protecting native grasslands.

“…We are feeding the world and protecting species at risk at the same time. [The public] need[s] to understand the pride we take in what we do. This is our passion, and it is not about money, there is not enough profit to be made.”

“I felt that we were managing our grass in such a way that it was a good fit for our operation to be recognized and rewarded for proper grass management.”

Though the ranchers were generally satisfied with the program, some said it would be more helpful if the programs were longer (this one was only five years), with better compensation.

“… I would like to see them be longer than five years; and I would like to see this funded wholly, for them to put more dollars towards it because if they would fund it, we would put more land in it. Again, recognizing that these are the best managers for critical habitat that we have, and we need to reward them for their work and keep them on the land.”

Ranchers see themselves as land stewards. They take care of the land that takes care of them.

“…yes, it’s all interconnected, the native grasses and the native species that are on those grasses, they were here first and we’re just utilizing the leftovers — call it the abundance — and so we have to manage it properly to support them, and if not, they won’t be here and we won’t be here either.”

Working Together

The Milk River watershed case study demonstrates that ranchers are willing to help protect biodiversity if there are fair, flexible programs in place with trusted organizations coordinating the program. Grazing can be a land-use that is compatible with grassland conservation and endangered species protection if ranchers have the financial and societal support to pursue it.

Learn more about how we are working on Saving Grasslands Through Sustainable Ranching

Authors

Dana Reiter, Lael Parrott and Jeremy Pittman