As spring arrives on the Prairies, many species are either waking up or migrating to their summer homes.

Here are three of our favourites — true superstars of long-distance migration. These migrating birds travel an average of 3,000 kilometres from their winter refuge to their Canadian breeding grounds!

1. Long-billed Curlew

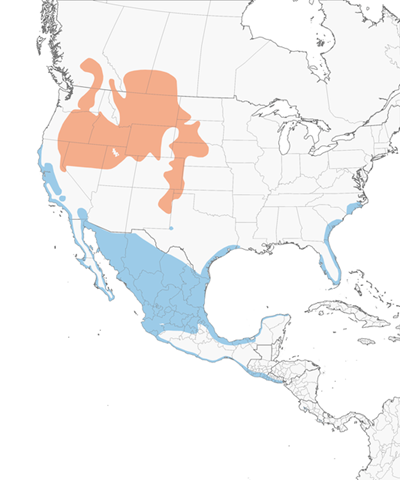

There are several odd things about the Long-billed Curlew. This large brown member of the sandpiper family has a strikingly long down-curved bill. But, despite being a shorebird, it shuns wet habitats during the summer, and seeks the grasslands of Saskatchewan, Alberta and British Columbia. This bird’s diet includes insects, crustaceans and worms. They use their long beak to forage on the surface and also to dig into soils to find soil dwelling food (like small crustaceans).

These birds weigh in at 580 grams (about 1.28 lb) and will fly an average of 3,000 kilometres in late August to eventually overwinter in California, Mexico and Central America. It’s on the southern beaches where they seem to be most at home. If you’d like to learn more, Hinterland Who’s Who has more on the life of the Long-billed Curlew here.

2. Burrowing Owl

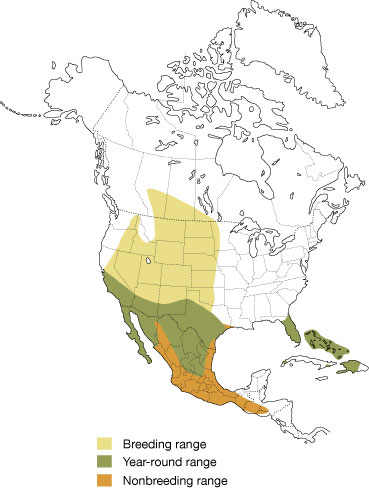

Winter on the northern Great Plains is hard. So, starting in September, Burrowing Owls embark on an amazing two-month, 2,500 to 3,500 km migration to southern Texas and Mexico. Weighing in at just 125 to 185 grams (the same as a yogurt cup), these owls face a strenuous journey.

Sadly, life is hard in their southern home. Most Burrowing Owls that travel south never return to breed in Canada the next summer. Scientists are unsure what happens to the 60 per cent that go missing. Do they move elsewhere or die? They do know that the Canadian prairie is also no picnic — 40 per cent of the chicks born in Canada die before migrating. There is still much to learn about Burrowing Owls.

This unusual owl shelters underground for protection from predators and the hot prairie sun. Its range primarily is in southern portions of Alberta and Saskatchewan. Avian predators include hawks, falcons, eagles and larger owls. Their greatest land threat are Coyotes.

Burrowing Owls are carnivores, foraging on insects, mice, birds and lizards. They are known to eat any vertebrate or invertebrate they can handle.

Declining habitat has earned Burrowing Owls the status of Endangered in Canada; part of the reason why the Canadian Wildlife Federation is working hard to protect their summer habitat: native grasslands.

Watch a video on the Burrowing Owl.

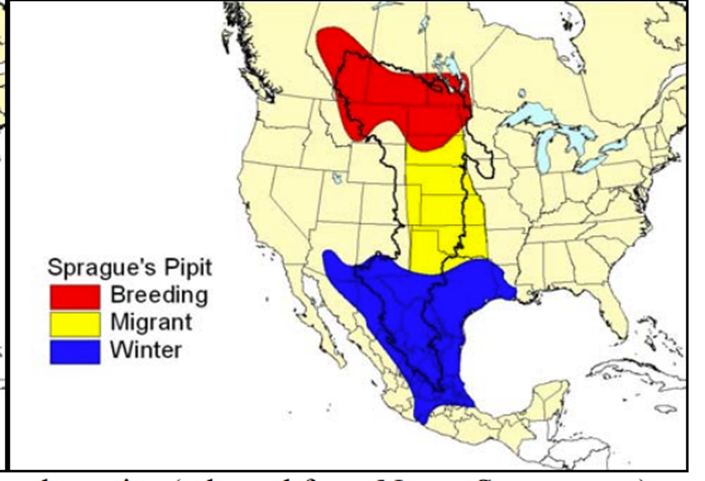

3. Sprague’s Pipit

This small grassland bird, weighing in at only 22 to 26 grams (think an AA battery), migrates 3,000 to 4,000 kilometres — no small feat given its size. It spends summers on Canada’s native prairie and winters in the southern central United States and Mexico.

The Sprague’s Pipit is tough to spot on the ground due to its brown plumage that blends perfectly against the grassy backdrop. Its habitat is open, native grasslands across the Canadian prairie, but can occasionally be seen breeding in ‘tame’ forage like hay. However, they prefer large, unfragmented areas in which to breed, which is getting increasingly rare. Conversion of prairie to cropland and pasture has reduced this habitat greatly.

Predators such as Northern Harrier, Black-billed Magpie, Striped Skunk, and even rodents are known to consume adults or eggs and nestlings.

The diet of Sprague’s Pipit is mostly insects and arthropods, such as crickets, grasshoppers, beetles, ants, flies and spiders. They can also eat seeds of flowers and grasses.

Did you know? Across North America, birds that depend on grasslands are in steeper decline than most other groups of birds. Nearly 60% of Canada’s grassland birds have disappeared since 1970.

All three of these species travel a remarkable distance between their wintering ranges and their summer breeding habitat in the Canadian grasslands. This requires a huge output of energy. All three rely on insects for a good portion of their diet, a resource that is under threat from agricultural pesticides. Discover what the Canadian Wildlife Federation is doing to study insects and their impact on grassland birds.

It is important that grasslands and the insect life they support are conserved so grassland birds have a home to come back to in the spring.