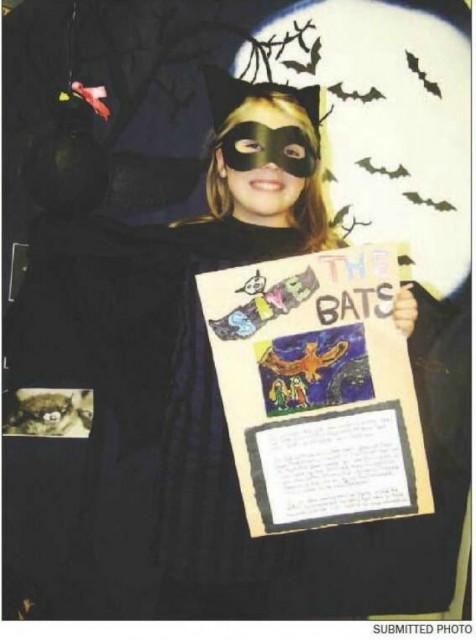

[PHOTO THE DAILY GLEANER FREDERICTON & REGION, MAY 22, 2013]

This summer I will have a chance to meet Dara Glasby, a grade 2 student from New Brunswick. Dara’s passion for bats and her efforts to save them are truly inspiring. Please read below the article from The Daily Gleaner from May 22, 2013 written by Laverne Stewart.

You can call her bat girl. An eight-year-old Harvey Elementary School student is doing something to help prevent the extinction of the brown bat in New Brunswick.

Dara Glaspy learned the bats are near extinction when her teacher, Cheryl McKillop, read a newspaper article to her class about the problem last fall.

The bats are dying from a fast-spreading disease called white-nose syndrome. The fungus that causes the disease has decimated the bat populations. Not harmful to humans and other creatures, the fungus spores that cause the syndrome have devastated bat populations throughout the U.S. and Eastern Canada.

Once Dara heard about the problem, she was determined to learn more. She started a research project on the brown bat and the disease. Since then, McKillop said, she’s been looking at ways to bring the problem to the attention of her class and the community.

“I heard that bats were becoming extinct and I really like bats. They’re cute and they eat a lot of insects. They help us. If we didn’t have bats, there would be an overpopulation of insects, and bugs eat crops. Bats are important to farmers and a lot of other people,” Glaspy said.

Dara and her father built a bat house from a design they found on the Internet, McKillop said. Together the girl and her teacher talked about taking a few orders for bat houses and making some money from them so it could be donated to bat researchers at the New Brunswick Museum.

“She wants people to be aware of having a bat house on their property. She can’t supply all the needs, but she wants people to be able to build their own or purchase their own. I’m actually her first customer,” McKillop said.

Glaspy said she hopes to raise $100 to send to the museum’s head of natural sciences, biologist Don McAlpine, to help pay for research expenses.

She said it might be possible to save the bats from extinction, but it will take everyone’s effort if they are to survive.

“People need to stay out of caves where they hibernate in the winter. People also need to be building bat houses,” she said.

McAlpine said he thinks it’s unusual for someone Dara’s age to have taken such a proactive interest in environmental issues, let alone bats, “which often have a high yuck factor for the general public.”

“If there is any hope that the many pressing environmental issues facing us today will be resolved, that hope lies largely with the Daras of the world. The problem is that there just aren’t enough Daras out there at the moment,” he said.

Her donation of $100 is one of many small donations McAlpine and other researchers at the museum use to fund the bat project, which requires more than $60,000 each year to run, he said.

“Every little bit helps… If more of us spent time even thinking about these problems, that would be a great start to really grappling with them,” he said.

McAlpine said Dara’s $100 donation could be used to pay for travel expenses to caves and mines where bat population surveys are done. It could also be used to pay for materials needed to do cultures of the fungi that live on bats,” he said.

“We are looking for fungi that might interact with the white-nose fungus. So every little bit helps.”

In an email to Dara’s teacher, McAlpine invited the girl and her parents to come to the New Brunswick Museum in Saint John to see the research on white-nose syndrome and to introduce her to research associate Karen Vanderwolf.

Vanderwolf said the risk of extinction of the brown bat is high, and she praised the girl’s efforts.

“I think that’s incredible. It’s so nice to hear that young people are getting involved in this. To have someone show this level of interest is really exceptional. I hope I get to meet her,” she said.

Vanderwolf said when Glaspy arrives at the museum, she will show her some of her bat research data.

Vanderwolf spends a lot of time going into caves and counting bat populations in the winter while they’re in hibernation.

“We started before white-nose syndrome came into the province and we have documented each year how they’re declined. They’ve really taken a huge hit… We had over 7,000 bats a few years ago and now we’re down to 79 this winter,” she said.

By next year, researchers such as Vanderwolf and McAlpine said the brown bat will likely be extinct in the region – the fastest extinction of a mammal group in the province.

“The best hope for them is that some of the bats will have a natural immunity (to white-nose syndrome) and that the population will recover over a period of time. In the meantime what we need to do is to reduce mortality through the life cycle for bats as much as we can,” McAlpine said.

If the brown bat has any hope of survival, everyone needs to get involved, he said. In the summer, people can help by not disturbing bat maternity colonies. Hot attics and barns are favourite roosting places for female bats and their babies. This is why it’s important to leave then alone until their offspring are able to leave the roost, Vanderwolf said.

Erecting bat houses could also help, she said, because it will give male bats a place to roost in summer.

“They will leave in late fall and then you can seal up any holes. There’s a lot of documentation on the proper procedures of humanely excluding bats from homes,” she said.

If you block the holes before the bats are ready to leave for their winter hibernation locations, you will end up with rotting bats in your attic and other buildings on your property, she said. The bats and their young will leave for their winter home in late August.

Bats spend their winters in caves and abandoned mines. Vanderwolf said people shouldn’t visit these areas because it’s detrimental to disturb hibernating bats. It’s also important to stay away from caves and abandoned mines so fungus spores aren’t spread from one location to another, she said.

It’s believed the white-nose fungus was spread from Europe to New York by travelers who picked the fungus up on their boots while exploring bat caves and unknowingly spread it once they returned to the U.S. From there it quickly spread to other states and Canada, she said.

Also gone in large numbers are the northern long-eared bat and the tricolored bat.

The near extinction of the brown bat spells trouble for the environment especially for the agricultural community and forest industry, which counts on these insect eaters to control the populations of insects, Vanderwolf said.

She and McAlpine aren’t optimistic about the bats’ future in the province, but they are encouraged by Dara’s efforts.