The end of August and start of September is a time of change.

Leaves begin changing colours and temperatures slowly (but surely) begin to lower. It’s also the time when the iconic Monarch Butterfly migrates south from Canada to their overwintering grounds in Mexico!

Every year, members of the Canadian Wildlife Federation terrestrial team conduct surveys for migrating Monarchs. This is done through mixed methods including point counts. This method allows the observer to spend at least five minutes in one position looking for migrating Monarchs and counting them. Point counts can be done anywhere within Monarch range, but we often focus on conducting counts in places like roadsides and hydro corridors.

Another important survey method is looking for Monarch roosts. Monarchs are diurnal migrants. This means they travel only during the day, take the night to rest and then start their journey again after dawn. Monarchs will often cluster together in trees along their routes, helping keep each other keep warm overnight. These clusters are called roosts and can sometimes consist of hundreds to thousands of individual Monarchs.

Main Duck Island

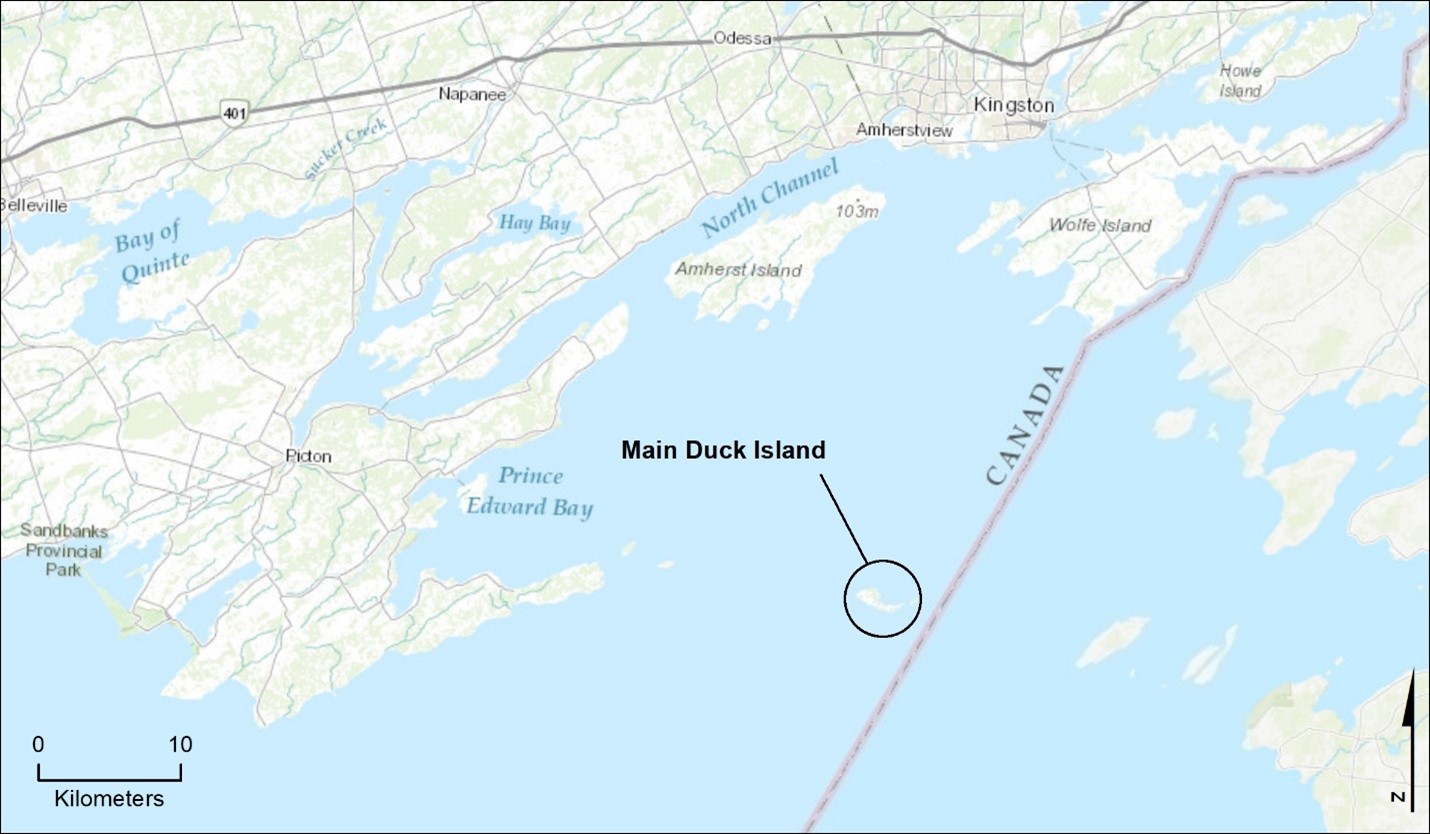

This year, CWF staff Vincent Fyson and Vicky Papuga, joined by volunteer Alex Stone, embarked on a trip to conduct Monarch point counts and roost surveys on Main Duck Island. This island is located on Lake Ontario, south of Prince Edward County. Main Duck Island is a Parks Canada property, part of the Thousand Islands National Park.

Our team wanted to survey the island because we had an idea that it might be an important stopover point for Monarchs. We supposed this theory because we know the Monarchs will travel over the Great Lakes but typically use islands for rest stops on their trajectory across water.

Day 1: September 3

We set off for an overnight trip starting on September 3, 2024, which we thought would be during peak migration for the area based on migration data from prior years. We had a boat charter that left from near Picton in Prince Edward County and took us out to the island, which took about two hours. Thankfully, the waters of Lake Ontario were fairly calm, and we had an experienced boat operator.

Once we reached this picturesque island, we took some time to do a little walking tour with our boat operator, who let us know there were some snakes on the island. We were fortunate enough to come across a large, beautiful water snake; these snakes can reach over a meter in length and are excellent swimmers!

After setting up our camp site, we started our surveys at approximately 3 p.m. with the goal of completing point counts along the length of the island, from the dock area in the southern half to the lighthouse at the northwest corner of the island.

Walking along an established trail, we worked our way north and arrived at the lighthouse around 5 p.m. On the way, we did not see any actively migrating Monarchs, but we did see about 100 Monarchs nectaring both on non-native purple loosestrife (Lythrum salicaria) and native goldenrods (Solidago spp.). We saw Monarchs nearly anywhere we observed the purple loosestrife, and it sometimes appeared that Monarchs preferred feeding on the loosestrife over goldenrod, when both plants were present.

We saw mostly Monarchs in two main areas of the island: in the north-west point nearby some abandoned buildings and the lighthouse, as well as on the southern section around the marsh, with some scattered individuals seen in between. We also saw many Monarch caterpillars (at least 16 individuals) primarily near the lighthouse, where most of the Common Milkweed was found.

Our walk back to the campsite was devoted to searching for roosts. We saw the first roost forming around 5:30 p.m. on a willow tree nearby the lighthouse, and thought it was likely there were other roost locations in that area of the island based on how the Monarchs were behaving. But we were unable to spot the exact roost locations.

We did not see any other roosts until we got back to the wetland area west of the docks, where we found four roosts that had more than 50 Monarchs in total! Our roost search ended at dusk.

Day 2: September 4

We began our surveys at dawn the next morning but did not see a lot of activity — even at the known roost locations — until about an hour after dawn. The path we followed was the same as the day before, going toward the lighthouse at the north-west corner of the island, making it there for around 8:30 a.m. On the way we saw some nectaring and migrating Monarchs, but not many.

The real spectacle began after we arrived at the lighthouse (although it may have already been happening without us observing it!). We watched as a steady stream of Monarchs flew off the tip of the island in a north-west direction toward Prince Edward County. We counted 25 Monarchs leaving the tip during a 30-minute point count. Most of the Monarchs seemed to initially be headed between a west and northwest direction but, due to a stiff breeze from the southwest, veered in a direction between northwest and north as soon as they were in the full wind, away from the protection of the island. Some Monarchs were seen flying out from the shore, up to 100 metres or more, and then circling back toward the island.

We were puzzled by the Monarch behaviour of heading north from the Island, rather than south, toward Mexico. Perhaps the route selection was due to the wind direction or some other migratory behaviour.

We left the lighthouse around 10 a.m. and observed a few other Monarchs on the return trip to our camping spot.

Opportunities for restoration

Based on our observations, it is clear the island is an important migratory stopover for Monarchs as well as other species! While we were there looking for migrating Monarchs and their roosts, we also observed an impressive array of bird species, including many species of warblers, sparrows, birds of prey, and, of course, ducks.

We noted that the island did not contain much in the way of nectaring (or feeding) resources for Monarchs. Migrating Monarchs require a substantial amount of nectaring resources to support their migration, as they need to stop and fuel up daily. Nectaring resources include those flowers that bloom in late summer into fall, such as our native asters and goldenrods.

Although meadow habitats were present on the island and contained some native species like goldenrods, much of the meadows were dominated by non-native and invasive species including Dog-strangling Vine (Vincetoxicum spp.), vetch and tame grasses. The most abundant floral resource was likely the Purple Loosestrife, which was found in wet areas and shorelines, followed by goldenrods found in small patches throughout the island.

Main Duck Island is clearly an important stopover for migrating Monarch Butterflies. Based on studying maps and data, we expected this to be the case. Next year we will try to solve other mysteries about the fascinating Monarch Butterfly and its great migratory journey!

If you want to learn more about how you can help contribute data about the Monarch’s migration, join the Kaleidoscopes Monarch Project!

If you want to learn more about CWF’s work to restore habitat for Monarchs, check out Help the Monarchs.

Authors

Vincent Fyson

Vincent Fyson

A critical component of conservation is understanding how a species interacts with its environment. My interest is in discovering how the biotic and abiotic components of a landscape influence its resident species. Additionally, I’m interested in how that knowledge can be used to direct conservation efforts to prevent the loss of biodiversity.

Vicky Papuga

Vicky Papuga

Vicky Papuga is the Rights-of-Way Pollinator Habitat Coordinator with the Canadian Wildlife Federation. After working in the field to restore meadows in urban spaces, Vicky fell in love with habitat restoration and hasn’t looked back. When she isn’t busy designing a seed mix or providing advice for a restoration project, you can find her outside looking for native seeds and wild critters, walking her (somewhat trained) cats on their leads, or playing boardgames with her partner and friends.