Many older residents of the Canadian prairies talk of seeing large numbers of Monarch Butterflies flying about in the summer.

This is hard to believe, since it is quite uncommon to see Monarch Butterflies in western Canada. Current estimates in the prairie provinces of Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba, show limited occurrence of this iconic butterfly.

However, in the past, it seems that the spread of the prairie portion of the Monarch population was much greater than it is today. One author (Brower, 1995) suggests that until the 1880s, the prairie region of North America had been the main breeding area of the Monarch Butterfly (Danaus plexippus). The native floral community consisted of 22 species of milkweeds (Asclepias family), which supported caterpillars and provided nectar for adults.

The theory goes that the plowing of the grasslands to create crops not only destroyed the grasslands, but also eradicated much of the milkweed resources.

At the same time, the forests of the eastern great lakes region were being cut for development. This allowed for the widespread growth of the Common Milkweed (Aslepias syriaca) in Ontario and Quebec. This allowed the Monarch to adapt its range to utilize this new open habitat for breeding.

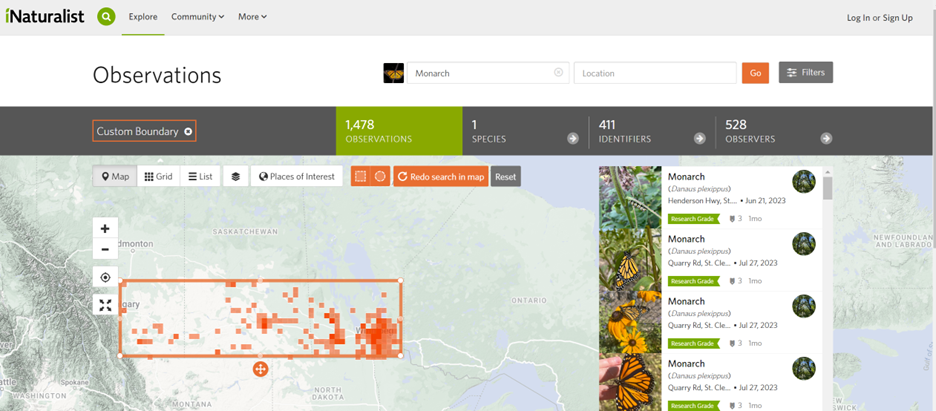

Today, in the prairies, there are very few Monarchs breeding and the range seems to be limited to the southern portions of those three provinces. Based on iNaturalist records, Monarchs are seen from Calgary in the west, and to the east in Winnipeg and bounded in the north in line running east to west through Humboldt, Saskatchewan. There were about 1,500 observations of Monarchs by 528 observers in this area over the last few years.

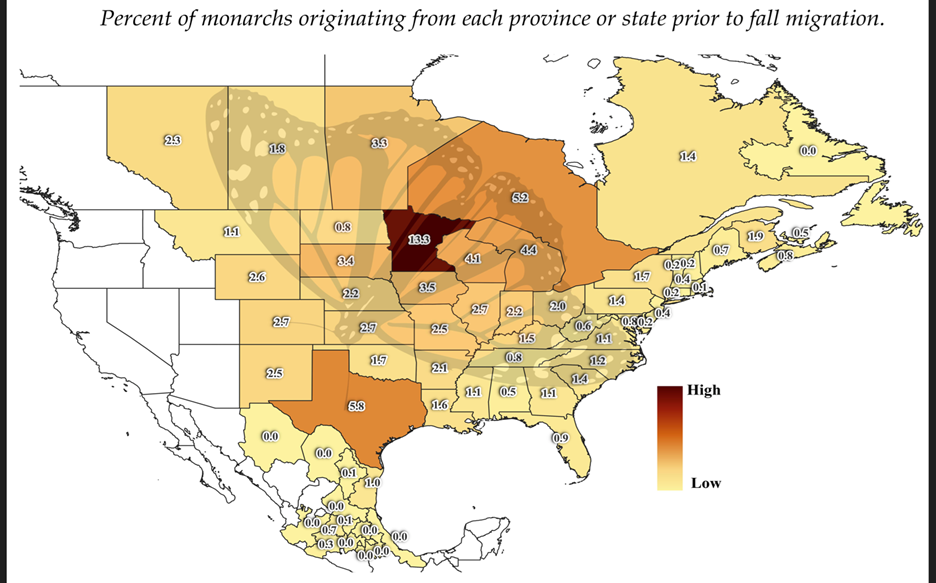

Other research confirms this, suggesting that the provinces of Alberta, Saskatchewan and Manitoba represent 2.3 per cent, 1.8 per cent and 3.3 per cent of the Monarchs travelling to Mexico each year.

iNaturalist Canada observations also show there are three milkweed species to be found in Alberta and Saskatchewan (Oval-leaved, Showy and Short Green Milkweed). Manitoba boasts two additional species likely found in more moist areas (Whorled, Common and Swamp Milkweed). Of course, this reflects data only collected in the last five years and may be lacking. Milkweed can definitely grow here!

This story of Monarchs in Canada over time illustrates the tremendous capacity of this species to adapt to landscape change. It makes me wonder, if we could restore grasslands to include milkweed species in abundance, could we increase the Monarch population? Could we see huge numbers of Monarchs flying to the prairies every year?

Not to mention the huge numbers of other pollinators that would be supported?

Given that only about 25 per cent of the original native grassland exists in Canada today, what could be achieved with restoration of grasslands?

History has lessons to teach.

Learn more about Canada’s grassland and how the Canadian Wildlife Federation is helping.