What if we could learn a lesson or two in survival from one of the Earth’s weirdest organisms? Lichen in our cities present a powerful metaphor for our biologically troubled times. Symbiosis anyone?

The Lipstick Powderhorn stands straight up in the air, green stalks tipped with lush crimson. Greyish-green curly biscuits frequent the sand, while golden moonglow lurk on tombstones.

These are species of urban lichen. And while the idea of urban lichen may seem like an oxymoron, it isn’t. In fact, lichens are in comeback mode in cities across the world after having been absent for about 100 years.

Consider the lichens of Paris. Back in the mid-1800s, the Finnish botanist William Nylander began cataloguing lichen species in the Jardin du Luxembourg, the lavish garden in the centre of Paris. He published a paper in 1866 describing 32. By 1896, when he did the lichen census once more, all had vanished. The garden had become a lichen desert.

Nylander wondered whether it was the air pollution blanketing Paris, the result of burning coal. It was an early scientific questioning of how much the quality of air matters to living creatures.

Generations of botanists continued the search for lichens in Paris, but it was almost a century before they found any. In 1986, the famed British lichenologist Mark Seaward found a single species clinging to the base of some trees in the Jardin du Luxembourg. By 1990, he and a colleague were overjoyed to count a total of 11.

What sparked the resurgence? With laws cutting down air pollution, air in the cities had become cleaner and fresher. Instead of killing the lichens, now the air was nurturing them.

It was the same story in New York, according to a field guide on urban lichens for northeastern North America by Jessica Allan and James Lendemer, published this fall by Yale University Press. In 1824, lichen aficionados counted 191 species in a 50-mile radius of Manhattan’s town hall. By the middle of the following century, almost all had vanished.

Enter the Clean Air Act of 1970, which governs air pollution across the United States. It has been so effective that today, about 100 lichen species are back in New York City, clinging to trees, sidewalks and gravestones.

Canada developed lichen deserts, too. In the 1960s, terrible air pollution had driven lichens from the streets of Montreal and Sudbury, just two of the Canadian cities where lichenologists kept track. Today, thanks to controls on such industrial toxins as sulphur dioxide, Canada has among the highest lichen wealth of any country in the world, with more than 2,500 species. Toronto alone boasts 138 species, the field guide says.

The resurrection of urban lichens tells a powerful tale about the effects of pollution, of course, and of the necessity of laws to control harmful compounds. But it seems to me there are other lessons embedded within the fragile flesh of these odd creatures.

Lichens are made up of at least two other organisms, typically a fungus plus an alga or cyanobacterium. Sometimes, a lichen is a combination of all three. They depend on each other, which means they are called symbionts.

When the creatures merge, they go through a process called “lichenization” to make the new lifeform. Think of the transformer robots children play with that can morph from one shape to another. The fungi provide the lichen’s new protective architecture. The algae or cyanobacteria form a layer inside and provide the food by photosynthesizing sunlight.

Weirdly, when botanists separate the lichen back into its components in a lab, those components thrive as the original fungus, alga or cyanobacterium, taking on the un-lichenized shape once again. Even more weirdly, it’s the fungus that holds the memory for metamorphosis. When it comes back into contact with its symbiont species, the fungus’s bent for becoming a lichen flips back on like a switch, and it begins the transformation again. The algae or cyanobacteria go along for the ride.

Once formed, the lichen is home to a whole universe of life: bacteria, other fungi, microscopic worms and miniscule Michelin-man-shaped tardigrades. And lichens feed many other creatures, including birds that make edible nests out of some of them.

It’s a powerful metaphor for our biologically troubled times, when a million species are currently at risk of extinction because of human actions. We are damaging the very life-support system of the planet.

What if the path forward is to think like a lichen? We depend on other species. They depend on us. It means humans are symbiont with the planet’s other forms of life. Together, we can make new realities, new communities of life. We can flip the switch.

Like the lichen, we can literally change the shape of the future.

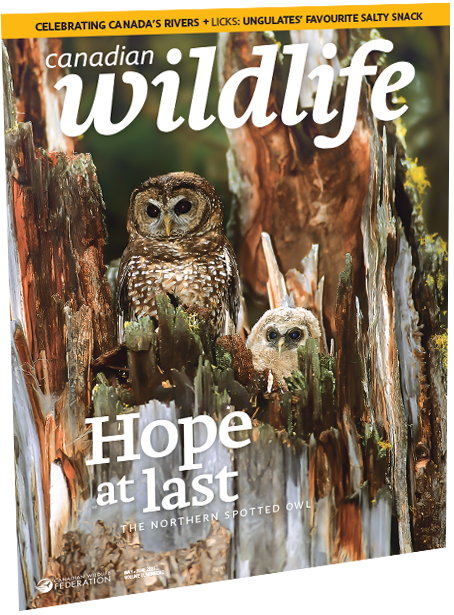

Reprinted from Canadian Wildlife magazine. Get more information or subscribe now! Now on newsstands! Or, get your digital edition today!